This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Ashes 1882: Death and WG Grace — the 10-minute mystery surrounding the match

August 29, 1882. England failed to get the 85 runs to win a spectacular thriller of a match and it resulted in the lore of The Ashes. However, was it only English cricket that had supposedly died that day? Did other deaths have some bearing on the result? Why were10 minutes mysteriously added to the innings break? Arunabha Sengupta looks at some myths and legends to unearth the truth behind the tales.

Written by Arunabha Sengupta

Published: Sep 20, 2013, 08:33 AM (IST)

Edited: Jul 07, 2014, 01:32 AM (IST)

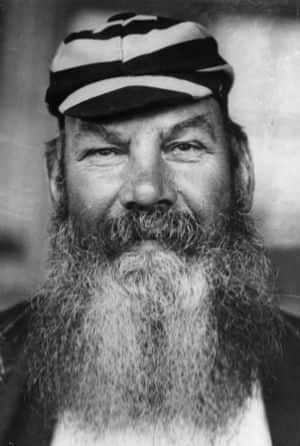

Dr WG Grace © Getty Images

August 29, 1882. England failed to get the 85 runs to win a spectacular thriller of a match and it resulted in the lore of The Ashes. However, was it only English cricket that had supposedly died that day? Did other deaths have some bearing on the result? Why were10 minutes mysteriously added to the innings break? Arunabha Sengupta looks at some myths and legends to unearth the truth behind the tales.

The legends of the last day

On August 29, 1882, giants clashed and sparks flew at The Oval. A story oft-repeated — by players, witnesses and historians, by cricket loving poets and one solitary mock-obituarist. The young journalist Reginald Shirley Brooks, writing under the pseudonym Bloobs for Sporting Times, declared English Cricket dead, thus immortalising the rivalry between the two nations in the form of ‘The Ashes’.

The tale of the match is laced with immortal anecdotes, of tension, frenzy, drama and heated words. And even death — not just of English cricket. Like most legends, some of it is true, and some fables have hitched on as the story has snowballed along the corridors of time.

Did Fred Spofforth really spew his vitriol at WG Grace? Were the English batsmen really given the instruction not to look at Spofforth as he had the ‘evil eye’? Did a spectator really die of heart attack due to the unbearable tension? And why was the break between innings on the last day much longer than normal?

It was that fateful day when the bowler with the demonic aspect and Machiavellian guile blasted the England batting out for 77 after the hosts had started out requiring just 85 to win. Moments before walking out, Spofforth had supposedly uttered the timeless line in the dressing room, “This thing can be done.” And WG Grace, his colossal form standing sentinel for the fortunes of English cricket, had not been able to carry his side home. After a superlative innings of 32, he had driven Harry Boyle a bit too early and the ball had spooned into the hands of Alec Bannerman at mid-off. England had slumped to 53 for four and could manage only 24 more after that.

The versions of the exact words spoken during the innings break remain somewhat inconsistent. However, it is obviously beyond doubt that the Australian players were incensed when Grace ran out young Sammy Jones. The young batsman was patting down some small unevenness on the pitch, the ball for intents and purposes dead for long.

According to Jack Massie, the son of Australian batsman Hugh Massie, his father had told him that a raging Spofforth had charged into the English dressing room, telling Grace that he was a bloody cheat, abusing him in the best Aussie vernacular for a full five minutes before delivering his parting shot, “This will lose you the match.”

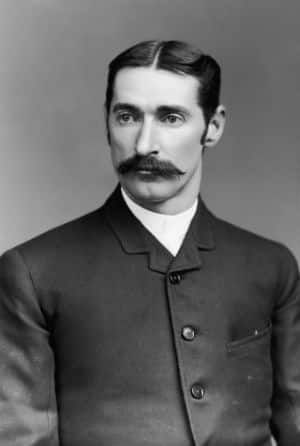

Did Fred Spofforth (above) barge into the English dressing room and call WG Grae a “bloody cheat”? © Getty Images

The Australian bowler Tom Garrett did not mention this exchange, but wrote that Spofforth had declared in their own dressing room: “I’m going to bowl at the old man. I’m going to frighten him out.”

And as WG Grace had come out to bat, the huge form of George Bonnor had looked him in the eye — the only one with the physical attributes to be able to do that — and had remarked, “If we don’t win the match, WG, after what you’ve done, I won’t believe there is a God in Heaven.” The great Australian hitter did not lose his faith.

As we will see later, Massie’s version is subject to a few lingering doubts. Even Garrett’s words could have been coated with a splash of colour by the passing of time. In 1882, the great Grace was a strapping man of 34. Would Spofforth have called him ‘old man’? One wonders.

However, as the match went on, there were indeed incredible scenes of excruciating tension. The players suffered from nerves strained to the limits, tactics became eccentric from feverish malfunctions of the brain. Spectators underwent frenzied moments of hopes and trepidation, perched at the proverbial edges of their seats throughout the two hours and two minutes of the final innings. An Epsom bookmaker named Arthur Courcy chewed halfway through the handle of the umbrella of his brother-in-law.

The English players popped open champagne bottles, not as means of celebration but as tonic for nerves. Charles Studd, with two hundreds against the Australians that summer, was kept back till No 10 by captain Monkey Hornby. The skipper kept mumbling, “I want to keep you up my sleeve.” AA Thomson later wrote, “So Charlie went up the sleeve and, alas for England, stayed there.

Studd himself, the fall of each wicket driving him to hysterical anxiety, wrapped himself in a blanket and walked round the pavilion. He did not face a ball after going in at the fall of the eighth wicket. Perhaps it was this game that induced him to migrate to China as a missionary.

According to CI Thornton, “[Allan] Steel’s teeth were all in a chatter; and [Billy] Barnes’s teeth would have been chattering if he had not left them at home.”

In the pavilion, Ted Peate had to be cajoled into tottering out to bat at the fall of the ninth wicket. A generous dose of champagne played a major role in making sure that he finally walked out and did so in a rather wobbly way. The hands of the scorer shook so much that Peate was scribbled as ‘Geese’ in the official scorebook.

With Studd at the other end, Peate heaved the first ball from Boyle past square-leg and ran two, when he could have stopped with a single to give the better batsman the strike. The next ball was targeted with an almighty swing that missed by yards, and Peate flashed a manic grin. Writers like Kenneth Gregory have wondered down the years: Had he been given too much champagne? Or had it been too little?

And finally he swung again to the last ball of the over, and unfortunately it eluded the willow and veered straight into the stumps. Boyle exulted and the English heads sunk.

“Why did you play a stroke like that?” asked his amateur colleagues in the pavilion, speaking to the professional with a touch of rebuke. And Peate responded, “I couldn’t trust Mr. Studd.”

“I left six men to get 30 odd runs and they couldn’t get them,” lamented Grace.

Death and the 10 minute mystery

There is also the quaintly horrific legend that a man died of heart attack during the last stages of the game, unable to withstand the tension. Tom Horan, who later wrote for The Australasian under the —pseudonym ‘Felix’ did his bit to embellish the story — handsomely adding to the chronicler’s time-honoured disdain for factual accuracy. Of course, while fielding at short leg to Spofforth, Horan was hardly in a position to form a proper idea of the happenings in the feverish stands, and one wonders how he documented rather graphic details of the excitement.

In Horan’s account, we find words describing the electric sparks of tension towards the end of England’s second innings when ‘the strain, even for spectators, was so severe, that one onlooker dropped down dead …’ HS Altham, and later Neville Cardus, borrowing heavily from Horan, did not mention the slight oddity that could shed light on the actual incident.

Even to this day, years after the reconstruction of the facts, the truth has not been repeated often. The original legend is perhaps too good a story to be killed like the unfortunate man in the stands. There is also the added peril of taking the sheen out of the Spofforth-Grace scene in the dressing room. Strange, because the actual facts have enough elements of interest for the cricket lover.

The death did not take place in the last stages of the match. It happened during the innings break.

Altham relied on what was normal to extrapolate his knowledge into the account of the game. He thus documented his history as: “the breathless 10 minutes that divided the innings.” So insignificant a detail need not be checked anyway, when bigger and greater things demand our attention.

However, if we look at the Wisden report, we find that the Australians ended their innings at 3.25 pm, after which Grace and Hornby started their response at 3.45 pm. The contemporary press reports of the day agree with Wisden. The break did stretch for 20 minutes. What caused this delay? Let us recreate the events as they unfolded.

That morning, as the scheduled start of the match approached, nearly twenty thousand made for The Oval. Among them was George Spendlove, a 48-year-old resident of 191 Brook Street, Kennington. He waved goodbye to his wife Eliza, secured his sandwiches, collected friend Edwin John Dyne from 24 Pollock Road, and headed towards the ground.

They reached the stadium just as the groundsman and his staff were removing mud from the creases and filling the holes with sawdust.

As Boyle was bowled by Steel and the Australian innings ended at 3.25, Hornby, sensing his finest hour, was mentally preparing himself to go in first with Grace. And as the men trooped back to the pavilion, Spendlove told Dyne that he was not feeling too well. He stood up, tottered and fell to the ground, blood pouring from the mouth.

A shocked Dyne cried out, “Doctor” and the yell was taken up and relayed by many of the other spectators nearby. And soon a doctor did loom over the crowd. He was a giant, had a thick beard and his crown was topped by the MCC cap. Yes, the nearest doctor who responded was none other than WG Grace himself. He took one glance at the patient and instructed, “Carry him to the room above the pavilion.”

Missives went out to the Australian dressing room, “WG professionally engaged. Won’t be long.” And hence the gap between the innings was extended.

Not that it took too long. Spendlove had suffered from internal haemorrhage. Although other doctors came up to examine him as well, he had already died by the time he was taken to the room. It remains debatable whether the sight of a dying man being examined by Grace had any effect on the England team and their subsequent capitulation, but the myth of the heart-attack during England’s chase is definitely false.

So WG had scrubbed himself, removing the grime and dirt of the field. He had examined a patient with haemorrhage and had pronounced him dead. He had washed himself again before putting on his pads, and had walked out with his captain to commence the innings. All this was done in the course of 20 minutes. There seems to be little chance of Spofforth coming in and shouting at the doctor while all this was going on. With a General Practitioner thus engaged, it seems somewhat bizarre for him to be shouted at, whatever be his on-field activities. In his excellently researched biography of Spofforth, Richard Cashman does mention that ‘The Demon’ was riled up by the act of Grace, but there is no account of the volley of Aussie abuse hurled at the doctor.

The truth is documented in precise terms in George Spendlove’s inquest. It took place in the Crown Tavern, Church Street, Lambeth. Mrs. Eliza Spendlove identified her husband. Mr, Edwin John Dyne gave his evidence. Mr William Carter, the East Surrey Coroner, reached a verdict of ‘Natural causes’. Dr. WG Grace was referred to as ‘the well-known cricketer’. The time of death was placed at approximately half past three in the afternoon.

Brief scores:

Australia 63 (Ted Peate 4 for 31, Dick Barlow 5 for 19) and 122 (Hugh Massie 55; Ted Peate 4 for 40) beat England 101(Fred Spofforth 7 for 46) and 77 (Fred Spofforth 7 for 44) by 7 runs.

TRENDING NOW

(Arunabha Sengupta is a cricket historian and Chief Cricket Writer at CricketCountry. He writes about the history and the romance of the game, punctuated often by opinions about modern day cricket, while his post-graduate degree in statistics peeps through in occasional analytical pieces. The author of three novels, he can be followed on Twitter at http://twiter.com/senantix)