This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Australia and West Indies play thrilling draw at Adelaide in 1969

The Australia-West Indies Test at Adelaide in 1969 could have had all three results possible.

Written by Arunabha Sengupta

Published: Jan 29, 2014, 05:06 PM (IST)

Edited: Nov 10, 2015, 04:14 PM (IST)

January 29, 1969. It was a dramatic end to a magnificent Test match where all four results were possible till the last few overs. Arunabha Sengupta looks back at the match at Adelaide which Garry Sobers called the most exciting he ever played in barring the Tied Test.

Dwindling powers

They had been on the top of the world, but the two battering rams with which they used to break through the defences of the opponent were growing weary and frayed.

The genius of Garry Sobers remained unabated. He topped the batting averages with nearly 500 runs in the series with two hundreds. He was second among the bowlers from West Indies, with only Lance Gibbs taking more than his haul of 18 wickets. Sometimes sparks of inspiration flashed in his captaincy on the field.

But, the two men who had struck fear in the hearts of batsmen around the world were past their best. Wes Hall and Charlie Griffith captured only eight wickets apiece in the series, both gaunt shadows of once lethal men.

There were some moments of brilliance from the batsmen, but apart from Sobers himself and Joey Carew, consistency was at a premium. Rohan Kanhai, Seymour Nurse and Roy Fredericks were erratic, with unsynchronised moments of excellence.

In the first Test at Brisbane, the exceptional cricketing acumen of Sobers was in display. Faced with a 200-run partnership between Bill Lawry and Ian Chappell, he casually tossed the ball to Clive Lloyd. The young Guyanese batsman soon dismissed both centurions, each time caught by the captain himself. In the second innings, Sobers bowled his slow left arm spin to capture six for 73 as Australia lost by 125 runs. The lore of the genius seemed to continue. As long as Sobers performed, he would win matches single-handedly. The Caribbean supporters rejoiced.

But from the Melbourne Test, things changed drastically. On a wind-lashed, bone-chilling first day, Lawry won the toss and put West Indies in on a green top. Garth McKenzie destroyed them with eight for 71. And the Lawry-Chappell pair batted them out of the game with a 298-run association. Sobers did his best yet again, taking four wickets, scoring 67 in the second innings, but in spite of his heroics West Indies lost by an innings.

The third Test at Sydney followed a similar pattern. This time Sobers won the toss and batted, but the side managed just 264 against some disciplined bowling. In reply, every Australian batsman apart from wicket-keeper Barry Jarman got into the double figures. John Gleeson and Alan Connolly added 73 for the last wicket. The 283 run lead was enough to ensure a 10-wicket win. The Australians were up 2-1.

The problems at the top

As they went into the fourth Test at Adelaide, the West Indians were dangerously demoralised. And strangely, the main problem was Sobers himself.

In desperate need to relax after continuous cricket around the year, the captain spent more and more of his time between matches teeing off on the links. Fielding drills were not arranged, younger players did not enjoy the benefit of his advice, team meetings were seldom held. Sobers himself had no problems in coming back to the game and giving it all he had. He expected his players to do the same. He expected them to produce their best when on the field, irrespective of circumstance, injuries or interpersonal problems. He himself could do all that, and he honestly had no idea that it could not be expected of everyone, even if they were members of a Test side.

The other problem was that Sobers had suddenly developed an urge to travel alone. He drove off with friends while the team followed without the captain. This was not unlike Wally Hammond of 1946-47. The respect for his supreme abilities as a cricketer remained undiminished among the players. He was also loved as a genuinely pleasant man. But, his off-field captaincy left much to be desired.

The battle

The Adelaide match was played without an injured Hall. Once again Sobers won the spin of the coin and elected to bat, and once again the events transpired in a scary image of the previous two Tests. West Indies produced yet another modest first innings score of 276, and even that would not have been possible but for two hours of unbridled Sobers genius.

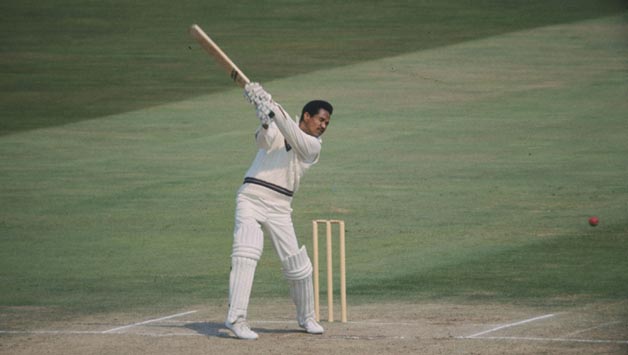

The West Indian captain walked in at 107 for 4 and batted with magnificent disdain. The strokes were unleashed with freedom of spirit and without restraint, an arc of marvel etched from backlift to follow-through. There followed 132 minutes of breath-taking batting, before he was bowled by Eric Freeman for 110. It was his 20th hundred, and scored in 117 minutes, with 15 fours and 2 sixes. The rest of the batsmen fell to a series of rash strokes, and West Indies were dismissed about an hour before stumps.

[inline-quotes align=”left”]This is the most exciting match I have played in next to the tied Test[/inline-quotes]

The Australian response was painstakingly familiar by now. Openers Lawry and Keith Stackpole scored 62 apiece. Ian Chappell got 76. Doug Walters slammed his second century on the trot. Almost all the top order got runs and the tail wagged as well. West Indies faced a deficit of 259.

At this critical juncture, for the first and only time in the series, the visiting batsmen got their heads down in unison. Carew batted four hours for 90. Kanhai’s blade flashed for a superb 80. Sobers followed his first innings hundred with 52. The hero during the first stage of the innings was Basil Butcher, who dominated the bowling during his strokeful 118. Lloyd got useful runs, while Nurse’s stylish and composed 40 was possibly the best knock of the innings. But, the poor selection of shots continued in the second essay as well, and when Lloyd fell to Connolly 25 minutes before tea on the fourth day, West Indies were 492 for 8. The lead was just 235, the wicket playing easy, a day and a half still to go.

Wicketkeeper Jackie Hendricks joined David Holford and produced a remarkable second wind of the rear-guard action. In 2 hours 20 minutes the two put on122. By the time McKenzie dismissed Holdford for a gutsy 80 during the dying minutes of the day, West Indies had passed 600 and were almost in the zone of safety.

Early next morning, McKenzie bowled Gibbs to end the West Indian innings at 616. That left Australia with an improbable 360 to get from almost the entire final day.

The chase

It was indeed a tough task, but the start that the home team got to their second innings ensured that there would be plenty of drama during the rest of the Test match. Lawry scored 89, adding 86 with Stackpole and 99 with Chappell. Posting 200 with only two wickets down, Australia sniffed a chance of closing the series with a victory.

As the Australians looked for quick runs, Ian Redpath was too eager to pinch singles. At 215, he was dismissed in controversial circumstances, Griffith running him out as he backed up too far in spite of warnings. But, by tea, Chappell and Walters had taken the score to 298 for 3. Australia needed just 62 from 15 eight-ball overs with 7 wickets in hand.

After the break, however, wickets started falling in a heap. At 304, Griffith, the ageing warrior, trapped Chappell leg before just 4 short of his hundred. Following this, in the span of 15 minutes, three men were run out. Walters, Freeman and Jarman were all caught short of ground, all three victims of some nervous calling and running by Paul Sheahan. Suddenly it was 322 for 7, Sheahan in the middle with only tail-enders for company. The wicket was still perfect. Just 38 runs remained to be scored.

McKenzie batted for 25 minutes, scoring 4, adding 11 for the eighth wicket, but at 333 his patience gave out. He slogged Gibbs down the throat of substitute Steve Camacho in the long boundary.

The batsmen had crossed and John Gleeson had to face the fired up Griffith in the next over. He found the pace too hot and was leg before off the sixth ball for a duck. At 333 for 9, Connolly joined Sheahan.

At this point, 26 balls remained. Eight years earlier, Ken Mackay and Lindsay Kline had thwarted the West Indians for ninety minutes to get a draw. Sobers, who had been there during the frustrating day, now had plenty on his hands. He had to decide whether to take the new ball during the last stages of the game.

The Caribbean captain did take the option, and proceeded to run in himself. And he wasted most of it, swinging seven of the balls too far down the leg-side. Griffith bowled the last over, his eight balls dead on target. And an ice-cool Sheahan blocked every one of them. With each delivery, the spectators let out a sigh of relief. The match ended in the tensest of draws with Australia on 339 for 9.

Sobers later remarked, “This is the most exciting match I have played in next to the tied Test.”

What followed?

The exceptional Test match notwithstanding, the West Indian challenge ended for all practical purposes. In the fifth Test at Sydney, Lawry with 151 and Walters with 242 batted them right out of the game. The huge total of 619 demoralised the visitors thoroughly and they succumbed to a paltry 279 in the first innings. The Test match being a six-day affair because of the undecided series, Lawry decided to bat again. Redpath got a hundred, Walters his second of the match — becoming the first man to score a hundred and a double hundred in the same Test. The ultimate target set for the West Indians was a farcical 735.

Sobers did attempt the impossible with another century, but in the end Australia took the series 3-1 with a 382-run win. The young Australian side had triumphed over the experienced West Indian line-up. Ironically, it had been the experienced that suffered from lack of guidance.

Brief scores:

West Indies 276 (Basil Butcher 52, Garry Sobers 110; Eric Freeman 4 for 52) and 616 (Joey Carew 90, Rohan Kanhai 80, Basil Butcher 118, Seymour Nurse 40, Garry Sobers 52, Clive Lloyd 42, David Holford 80; Alan Connolly 5 for 122) drew with Australia 533 (Bill Lawry 62, Keith Stackpole 62, Ian Chappell 76, Ian Redpath 45, Doug Walters 110, Paul Sheahan 51, Garth McKenzie 59; Lance Gibbs 4 for 125) and 339 for 9 (Bill Lawry 89, Keith Stackpole 50, Ian Chappell 96, Doug Walters 50).

TRENDING NOW

(Arunabha Sengupta is a cricket historian and Chief Cricket Writer at CricketCountry. He writes about the history and the romance of the game, punctuated often by opinions about modern day cricket, while his post-graduate degree in statistics peeps through in occasional analytical pieces. The author of three novels, he can be followed on Twitter at http://twitter.com/senantix)