This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

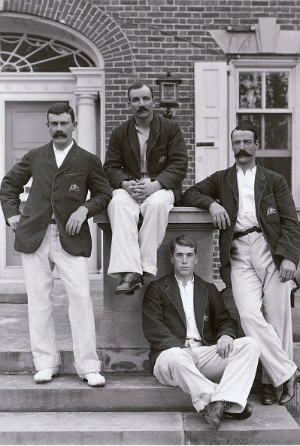

Ernie Jones and his supposed brush with Bodyline

Incited by bumpers at the body bowled by Gilbert Jessop, Ernie Jones supposedly retaliated and bowled near Bodyline at Cambridge University batsmen.

Written by Arunabha Sengupta

Published: Nov 27, 2017, 11:43 AM (IST)

Edited: Nov 27, 2017, 11:41 AM (IST)

June 10, 1899. Incited by bumpers at the body bowled by Gilbert Jessop, Ernie Jones supposedly retaliated and bowled near Bodyline at Cambridge University batsmen. At least, that is what Joe Darling claimed. Arunabha Sengupta recounts Darling’s story and checks other sources to verify whether any such thing actually took place or not.

It is a timeless tradition for cricketers to be constrained by their own time-spans when digging through their memories and coming up with the superlatives.

Hence, we can perhaps take Joe Darling’s proclamation “Ernie Jones was a better fast bowler than Harold Larwood” with several pinches of salt.

Every generation of cricketers tends to feel that theirs was the phase when cricket hit its magnificent peak, they don’t make them like that anymore and all that rot; along with there being too much money in the game today, modern players being too commercial yadda yadda yadda … This particular trait remains invariant over decades, even centuries.

And then, Darling was for long the caring and crafty captain who got the best out of Jones. He prodded him to bowl faster and faster by pricking his ego, asking the wicketkeeper to stand up, or surreptitiously informing him that the batsman who just came to the crease thought he was medium fast. It is quite natural for Darling to have a soft spot for Jones.

Also, Darling was an Australian, and therefore rather overly critical of Larwood after the 1932-33 series. This is what he later wrote: “There were plenty of good fast bowlers every bit as fast as Larwood and they always used to bowl a ball every now and then at the batsman just as Larwood did, but not so frequently, and with only one man on the leg side whereas Larwood had eight men fielding on the leg side.”

Yes, the observation about the field is spot on. However, it is rather hard to digest that there were ‘plenty of good fast bowlers every bit as fast as Larwood’.

Darling also maintained, “I am firmly convinced that if Jones had bowled like Larwood did with a packed leg field, then someone would have been killed.”

The main reason Darling forwarded for placing Jones ahead of Larwood was: “[Larwood] had to be spelled after bowling four or five overs, whereas Jones could bowl for an hour stretch without losing pace.”

When we look at the statistics, Larwood plodded along in the concrete-like wickets of the 1920s and 1930s, was forced to employ Bodyline out of the near-inhuman imbalance between bat and ball, and still averaged 28 for his 78 wickets. Jones sent down his thunderbolts in the era of dicey wickets, between 1894 and 1902, and even then could only scalp his 64 wickets at 29.01. It is very difficult to believe that he was better than the Nottinghamshire miner.

But, then again, take away the Bodyline series and Larwood’s average shoots up to 35, and then the romantics from that between-Wars era don’t quite know which way to look.

So, the comparison may not be that easy. And it is not the objective of this article to compare. Larwood struck Don Bradman on the hip. Jones sent a ball through the beard of WG Grace. That is enough for us.

The goal here is to recount the claim of Darling that Jones brushed with Bodyline bowling himself.

What happened at Fenner’s?

It was in 1899, and the touring Australians were cruising through their second month in England. The first Test at Trent Bridge, the one that saw Grace for the last time and Victor Trumper for the first, had already been played.

The touring side had gone down to Fenner’s to take on Cambridge.

Cambridge in those days contained a young fast-bowling all-rounder who could give the ball a tremendous whack. He went by the name Gilbert Jessop, and had a curious crouching stance. According to contemporary reports, this man, who was already a renowned hitter and would gain immortal fame after his match-winning century at The Oval in 1902, was also one who bowled really fast and sent down rather dangerous bumpers.

What took place when the Australians met Cambridge in early June is something of a mystery. Darling claims in his writings, later published in book form by his son DK Darling, that this was the match in which Jessop’s antics with the ball prompted Jones to bowl at the batsmen.

However, FS Ashley-Cooper’s mention of the game in Cricket says nothing extraordinary about the bowling of either Jessop or Jones, apart from a comment that the University men were done in by Jones and Howell. This last comment is as much about their bowling as their whirlwind stand of 85 in 25 minutes.

The staff reporter who covered the match for the magazine did say Jessop bowled very successfully, and also added that there was nothing terrifying about Jones’s bowling other than it was extremely fast.

In The Croucher, that excellent biography of Jessop penned by the most meticulous of researchers Gerald Brodribb, the report of the match is not that pronounced.

There is a mention of how the University went neck and neck with the Australians in the first innings, aided by the successful bowling of Jessop, after which there was a dinner given at Christ’s College by the CUCC for the visiting Australian side.

Jessop proposed their health with the Provost of Kings, and they had a full course meal starting with Consommé a la Sevigne, going on to Poulet Printaniers and ending with Croutes a la Bordelaise and Dessert.

Also related is the incident of umpire Mordecai Sherwin betting Jessop that he would be in the Test side because of the bowling. Jessop did not believe it and took the wager, and within a fortnight he had played in a Test as the sole fast bowler, and Sherwin had become the owner of a brand new hat.

To come back to the match itself, the University faltered in their second innings and lost by 10 wickets.

However, amidst all these innocuous reports of the game, Darling makes the claim that Jessop bowled at the batsmen and Jones retaliated.

Let us briefly sketch what took place in the match.

Cambridge University got 436, helped by138 by opener Leo Moon and 110 by wicketkeeper batsman Tom Launcelot Taylor. Captaining the side, Jessop got 13. In response, Clem Hill hit 160, Syd Gregory 102, Jones and Howell put on 85 and the Australian total was exactly the same as the Cambridge men. Jessop finished with figures of 6 for 142.

In the second innings, it was Howell’s 6 for 61 which spelled havoc. He was aided by Jones who took 2 for 48. Jessop was out for 11, and Taylor, the first-innings centurion, retired hurt. Jack Worrall and skipper Darling then stitched together 124 runs without being separated, thus guiding Australia to a win by 10 wickets.

Darling however states something which none of the other contemporary reports mention: “Jessop was deliberately bowling at the Australian batsmen and hit several of us on a fiery wicket. [Cricket’s report says that the wicket was perfect]. Jones retaliated, with the result that a batsman by the name of HL Taylor [sic] [a mistake, it was the same TL Taylor mentioned above. No other Taylor played in the game] was carried off the field and confined to his bed for over two weeks. Jones had only two men on the onside and goodness knows what would have happened if he had been told to bowl the same as Larwood did with a packed leg field.”

Given that Darling was recounting the event three decades and a bit after the actual occurrence, and then too with the horror of, and resulting disgust for, Bodyline fresh in his mind, his memory seems to have been clouded or coloured more than a bit.

In the delightful autobiography of Jessop, A Cricketer’s Log, there are one-and-a-half paragraphs devoted to the match, but neither the bowling of Jones nor Jessop himself is dealt with. It is rather the batting of Jones and Howell that is mentioned, and the centuries by Taylor and Hill. If Taylor had indeed been laid out that way by Jones, it is surprising that neither Ashley Cooper, nor Jessop nor the staff reporter of Cricket mentioned anything about it.

However, Darling claims that Jones bowled near Bodyline that day and it is a pretty impressive story. And spiced up by the ‘if only players of my time had resorted to this’ ingredient, it has the decipherable ring of rosy retrospection.

Evidence does point to this being a figment of reconstructed imagination in the head of the ex-Australian skipper. But, like any other cricketing legend, it has a nice wholesome ring to it.

Brief Scores:

TRENDING NOW

Cambridge University 436 (Leo Moon 138, John Stogdon 43, Tom Taylor 110; Monty Noble 4 for 105, Bill Howell 4 for 91) and 122 (Bill Howell 6 for 61) lost to Australians 436 (Clem Hill 160, Syd Gregory 102, Frank Iredale 40, Ernie Jones 53, Bill Howell 49*; Gilbert Jessop 6 for 142) and 124 for no loss (Joe Darling 60*, Jack Worrall 53*) by 10 wickets.