This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Googly bowlers, Dave Nourse, Percy Sherwell engineer South Africa’s first ever win in a heart-stopping Test

It took them 16 years and 12 Test matches, but South Africa finally achieved their first ever Test victory, that looked destined to go down as another defeat till the very last moment.

Written by Arunabha Sengupta

Published: May 18, 2016, 05:03 PM (IST)

Edited: Jan 03, 2018, 09:51 PM (IST)

January 4, 1906. It took them 16 years and 12 Test matches, but South Africa finally achieved their first ever Test victory. And it was a heart stopping thriller that looked destined to go down as another defeat till the very last moment. Arunabha Sengupta recalls the day the battery of googly bowlers, and some splendid batting by Dave Nourse and Percy Sherwell, snatched an incredible win for the Springboks.

Rumours and Reassurance

After the shock defeat to Transvaal, rumours did rounds in the Johannesburg press that England had sent an urgent cable summoning the great Yorkshire all-rounder George Hirst.

But then, that’s all what it was. A rumour.

Without the likes of Hirst, Wilfred Rhodes, CB Fry, Johnny Tyldesley, Tom Hayward and Stanley Jackson, it was certainly an English side of rather questionable strength. Only David Denton, Schofield Haigh and Colin Blythe remained of those who had taken part in the successful summer Tests against Australia.

However, the Englishmen never quite expected a strong challenge from the South Africans. A group of enthusiastic cricketers bankrolled by some Randlords, that’s all they were, wasn’t it?

But, the surprise defeat to Transvaal shook them. The battery of googly bowlers wasmore than a handful, especially on the matting wickets that made their balls turn twice as much as on turf. And the odd ball bounced as well.

As captain Plum Warner noted, it was extremely difficult to jump out to drive a ball as well, because the matting seemed slippery and there was the additional danger of finding one’s right foot caught in the end of the matting.

[read-also]330554[/read-also]

Yet, as they played the XVIII of Western Transvaal just before the first Test, some of their fears were laid to rest. The match was won by a whopping margin of an innings and 110 runs. Blythe captured 8 wickets, Haigh 7, Jack Hartley 10, young Jack Crawford 7.

In the second innings though, Crawford did definitely benefit from old Repton connections. The standing umpire was the Nottinghamshire-born Alick Handford, now a Johannesburg club professional, who had once coached Crawford at Repton. When the 20-year-old all-rounder hit the pad of R Oosterhuizen, the official gently leaned towards the young bowler and whispered, “Why don’t you appeal?” Crawford promptly shouted, “How’s that?” And Handford answered, “Out,” before adding, “Well bowled, good old Repton.”

This aside, Warner struck 125, his first hundred of the tour. Fred Fane scored 63. Hence, the team gave the impression of having recovered from the sudden upset.

Old Wanderers and New Test players

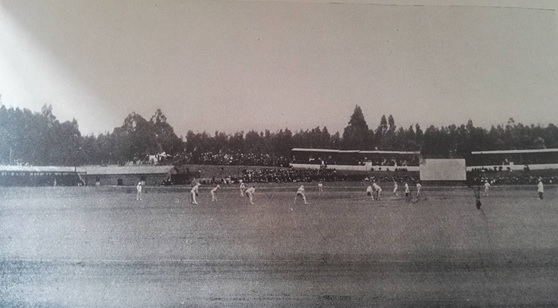

The Old Wanderers ground was filling up with spectators when Warner walked out to toss with Percy Sherwell on the second day of 1906.

The peacock-blue matting provided a striking contrast to the red-brown sand of the outfield, while long hedges of green bordered two sides of the ground. A giant screen stood at the railway end over which gigantic gum trees towered in menacing splendour. Sherwell flipped the coin up against the brilliant blue sky and Warner called correctly. England batted.

The South Africans opened their bowling with the wreckers from Transvaal, Reggie Schwarz and Aubrey Faulkner.

[read-also]212464[/read-also]

Since they had not played a Test match since 1902, both Schwarz and Faulkner were making their debuts. In fact, the Eastern Province leg-break googly bowler Bertie Vogler was playing his first Test as well, as was the other googly exponent in the line-up, Gordon White. This last named was a brilliant batsman, called upon occasionally to send down his wrist-spin. It was Schwarz who had picked up the tricks of the trade from Bosanquet during his sojourn in Middlesex, and he had passed on the knowledge to the rest of them.

Also making their debuts were the medium paced all-rounder Tip Snooke and the captain and wicketkeeper Sherwell himself. Of all these men, Faulkner was the genuine rookie. Just 23, he had played only four First-Class matches before the game. But, he had shown tremendous promise.

England too had a long list of debutants, the depleted side providing opportunities for Fane, Ernie Hayes and Walter Lees to play their respective first Tests. And additionally there was the hugely talented young Crawford.

January 4, 1906. It took them 16 years and 12 Test matches, but South Africa finally achieved their first ever Test victory. And it was a heart stopping thriller that looked destined to go down as another defeat till the very last moment. Arunabha Sengupta recalls the day the battery of googly bowlers, and some splendid batting by Dave Nourse and Percy Sherwell, snatched an incredible win for the Springboks.

The ten new men could not have asked for a more dramatic introduction to the highest form of the game.

Wickets fall like ninepins

It took just eight minutes for the googly bowlers to strike. Schwarz, who eschewed the leg-spinner completely and turned his balls only from the off, snared Warne. Trying to attack the captain was out spooning one to Snooke.

Denton, who had scored a superb hundred against Transvaal, felt in fine fettle and hence drove the first ball he faced. Faulkner moved like lightning close-in on the on side to catch him one handed. It was not ten minutes into the game, people were still streaming into the ground, and England had lost two men.

Soon Schwarz returned the compliment for Faulkner. Fane, struggling and strokeless, flashed at one from the youthful all-rounder and was caught by the wrist-spin mentor on the off-side. 15 for 3.

Captain (later Major) Teddy Wynyard, and Hayes steadied the ship somewhat before Sherwell introduced the third googly bowler. And Hayes hit one straight back to Vogler.

After an hour and quarter’s resistance, Wynyard jumped out to Schwarz and was fooled by a top spinner. Sherwell whipped off the bails.

The wicketkeeper-captain now introduced the fourth googly bowler. Albert Relf misread a wrong ’un and was bowled by White.

97 for 6. The googly bowlers were on rampage on the tricky matting wicket.

But young Crawford was still there. And Haigh was missed early in the innings. The Surrey all-rounder displayed a lot of confidence and skill, bringing off some superb strokes on either side of the wicket, hitting the ball hard and well. Haigh also hit freely. 48 important runs were added before Faulkner spun one back to bowl the Yorkshire man.

Having batted valiantly for an hour and a half on debut, Crawford finally fell to the pace of Jimmy Sinclair. Used in short bursts, the champion all-rounder got the young man caught in the slips for 44.

Lees walked out and hit two grand boundaries before White lured him out once again and Sherwell took the bails off with the Surrey paceman a quarter of the way down the pitch.

And Blythe batted with spirit, scoring faster than a run a minute, driving three well timed boundaries before Sinclair was summoned back to knock over his stumps.

The mighty — well, at least by reputation — England side were dismissed for 184. In just over three hours. It had been a grand team effort by the exponents of the googly. Schwarz had bowled 21 overs to pick up 3 for 72. Faulkner was learning fast, accurate, miserly, full of variations as he ended with 2 for 35 from 22. Vogler had 1 for 10 from 3. White 2 for 13 from 5. Sinclair’s pace had accounted for 2 for 36 from 11.

But, by the end of the day, the local supporters had little to cheer for. Lees found the wicket ideal for his medium pace, and Blythe turned the ball quickly and a lot. They went on over after over and the wickets toppled one after the other.

The reliable Louis Tancred snicked Lees to the keeper. William Shalders, one of the heroes of the Transvaal win, slashed at Blythe and was caught. Christopher Hawthorn had his stump uprooted by a Lees delivery.

From 13 for 3, White and Snooke batted with plenty of patience, the strategy clearly to tire the bowlers toiling under the fierce sun. But Lees and Blythe went on bowling relentlessly. And at 35, Lees had White caught in the infield.

It was at this crucial juncture that the six-foot-four form of Jimmy Sinclair walked out. Till then he had been the only South African to score a Test hundred and he had hit three of them. All of them had been spectacular exhibitions of hitting.

As the figure, ‘from a distance all arms and legs, and on closer inspection a magnificent breadth of arms and shoulder’, walked out, a great cheer was heard from the crowd. They were sitting in rows of five or six by now, round the cycle track that circled the ground. Here was the hero who would knock the professional bowlers off their nagging length.

There was a hush as Lees started his run up. The first ball was fast, short and Sinclair swatted at it. It soared in the air, Lees got under it as Warner shouted, “Catch it Walter.” Sinclair walked back. 35 for 5.

At the other end, Snooke, after three quarters of an hour of battle, got a touch off Blythe. And Faulkner, the magnificent Faulkner, blocked several, hit a boundary, and was fooled by a Blythe delivery that went with the arm.

44 for 7. Dave Nourse, the grand old man of South African cricket, was joined at the wicket by Vogler. It was the moment for desperate measures. And Vogler did as much. Blythe was lofted for four across the quick outfield. And then there was a huge on drive that landed on the green hedge for a great six.

[read-also]89114[/read-also]

62 for 7. Warner made the first change. Young Crawford was tossed the ball and caught it with childlike fervour. He marked his run for off-spin, not his medium pace. And his first ball in Test cricket turned and knocked Vogler’s leg-stump into the sand. What a debut!

Schwarz walked out to play out time with Nourse, and at six o’clock the players walked back with the score reading 71 for 8. The home team were on the ropes, but there had not been a single dull moment in the day.

A steep target

The next morning the end was not prolonged.

Crawford changed to his medium paced version, and Schwarz was brilliantly caught by Relf at second slip. Sherwell, too good a batsman to come in at No 11, nevertheless scored only a single in the 20 minutes he stayed at the wicket. Nourse, left-handed, big and loose-jointed, had been born in Croydon and had fought for the British Army. He remained unconquered on 18, scored over an hour and a quarter. He would have a far more important role to play in the match.

The total was 91. The lead was 92. The tale was one of oft repeated surrenders.

The variety of the South African attack enabled them to open the bowling with the medium pace of Snooke. And Fane was castled with the score on 3. But thereafter England enjoyed a period of consolidation. Denton struck boundary after boundary, off Schwarz and Snooke, testimony to his grand form. Warner looked comfortable and correct at the other end. The score went past 50, Denton quickly into his 30s.

And then young Faulkner ran in with his few short steps and indefatigable action. The ball pitched well outside the off-stump, went through Denton’s defences and hit the middle.

With Schwarz not effective in this innings, Vogler was summoned early. And he fooled Wynyard as the ball struck his stumps. 56 for 3.

After twenty minutes of keen tussle between bat and ball, Snooke was reintroduced as change of place and Hayes hit him down the throat of Schwarz.

Crawford was in at No. 6 and played splendidly yet again, his free upstanding style impressing everyone. The boundaries flowed, Warner progressed serenely to his half century. 40 runs were added in 50 minutes. England were past 100, the lead growing to serious proportions. Warner, who confessed later on that he had visions of a big innings flit through his mind, now played on to Vogler. 113 for 5.

But Relf was a handy man at No. 7. Having served Sussex with plenty of distinction, his appearances for the country had been limited. Yet, when called upon he had responded well. In 1903, in his first ever Test, he had added 115 for the ninth wicket with fellow debutant Tip Foster. By the end of his Test career he would open the batting and also dismiss Warren Bardsley, Warwick Armstrong, Victor Trumper, Monty Noble and Syd Gregory at Lord’s to take 5 for 85.

This useful cricketer did not look at ease, butmanaged to steady the innings with Crawford, playing the googly bowlers with pluck. In the meantime, Crawford continued to strike the ball handsomely through the covers, mid-off and mid-on. The score sauntered forward, and at 160 for 5 the match looked all but secure for the Englishmen.

But now Sherwell dug into the infinite all-round resources of South Africa. Nourse was given the ball, the seventh bowler tried, to bring his immense experience into play. The left-armer delivered fastish stuff from round the wicket. Crawford missed the line and was bowled for 43. Nine boundaries had etched this excellent innings.

Haigh and Relf scrambled 8 leg-byes in a curious phase of play. And then Nourse sent one in straight and struck Haigh’s pad. The finger went up.

The breakthroughs achieved, Faulkner was summoned to fox the tail. Wicketkeeper Jack Broad was caught plumb off a googly, Relf played a dreadful stroke to be caught at the wicket and Blythe was bowled first ball.

The end of the English innings was reached all of a sudden. From 165 for 6, it was suddenly 190 all out. The home side was left with a steep target of 284 to win.

The stuttering chase

In walked the South African openers. And the start was quite disastrous yet again. Tancred was caught off Blythe. Hathorn snicked to second slip off Lees. The score was 22 for 2. Inevitable defeat writ large on the wall.

Gordon White is often clubbed with the googly bowlers of that famous South African era. However, one tends to forget that he was a superb batsman with a delectable sense of timing. And Shalders had proved himself often enough in the past.

The two steadied the rocking ship, played off Blythe and Lees. Crawford was unable to find his control, and Haigh, after sending down one over, started feeling ill. Relf was pressed into the attack early. He was bowling off-breaks, getting quick and useful turn.

White, with extraordinary defence, seldom looked like giving the bowlers a chance. Shalders struck a few handsome boundaries. By the end of the day, the position of South Africa looked significantly better at 68 for 2. However, not many gave them much of a chance to overhaul the English total.

Yet, plenty of them assembled the following morning to watch the Springbok chase, among them the High Commissioner and the great South African cricket financier Abe Bailey.

And immediately on resumption, tragedy struck. Shalders went for an unnecessary single and was run out without addition to the score.

Haigh was half a mile away, ill in his bed. But Lees and Blythe bowled admirably and well. Snooke joined White and put up a fight for half an hour. And then he missed a straight one from the persevering Surrey paceman and was leg-before for 9.

Up went a great roar as Sinclair stepped in. He responded with a good strike for a boundary. And then he heaved mightily at Lees. The ball went high in the air and was caught magnificently by Fane at long on. 89 for 5. Surely this was the end of the challenge?

Faulkner was the new man in. A boundary was struck. The score inched past 100. A psychological landmark? And then inexperience of youth was in evidence. A misjudged call, a scamper and Faulkner was walking back, with the morose shake of his head. His role on his Test debut had ended. He had bowled superbly for his 6 wickets, but his batting greatness would have to wait to be revealed to the world.

The miracle

105 for 6. Miles and miles to go. It looked hopeless. Nourse was the new man in. Two men at the crease with impregnable defensive qualities. And suddenly they were making runs as well. Patiently, without risks, but the runs were coming slowly and surely.

Lees ran in and pitched up. Nourse drove. The chance flew to Relf at second slip. It would have been a spectacular catch if it had come off. A hand did reach the ball, but it did not stick.

White did not look like getting out at all. The philosophy of his innings was to be there at the wicket and wait for the runs to come. It was bearing fruit.

By lunch time the game was still heavily loaded in favour of England, but the hosts had made up a lot of ground.

Crawford did not bowl as well as he had done in the first innings. Haigh was sorely missed. Lees, Blythe and Relf did most of the bowling. Wynyard was tried for a few overs.

The breakthrough did not come. White was past his fifty and progressing slowly and surely. Once in a while the brilliantly timed drive was unfurled. But mostly it was superb defense and judgement. The bowling was worn down. Hayes was not a bad leg-spinner for Surrey, but perhaps not of the quality to bowl in Test matches. However, he was given the ball.

The South Africans were inching along, Nourse and White knocking off the runs with increasing assurance, to the alternating breathless hush and tumultuous cheering of the spectators.

121 had been added in two-and-a-quarter hours before Relf produced a special ball to hit White’s stumps. A great innings of 81 came to an end, essayed over four hours and ten minutes, with 11 boundaries. 226 for 8. The two batsmen had done yeoman’s work, but the victory target was still 58 runs away.

Hayes was persisted with, perhaps because of the spectacular success of the wrist spinners of the South African attack. And it did pay off. Vogler was bowled at 230. Two wickets to go. 54 runs to make. The left-handed Nourse was still battling at one end.

Nine tense runs were added and then it was time for a welcome tea break. The score read 239 for 8. None of the spectators dared to leave the ground.

England resumed with Relf and Hayes. And almost immediately a ball from Relf kicked up, and Schwarz could only hit it back to the bowler. 239 for 9. Still 45 to score.

Surely now victory was England’s? But as Warner wrote, “The odds would have been almost anything on MCC had the last man on the South African side been of the caliber of the usual eleventh man. But Sherwell is an extremely good bat.”

Indeed, when South Africa would visit England in the summer of 1907, he would open the batting at Lord’s and save the Test with a century. Quite a handy batsman to have as a No. 11. The first ball he faced from Relf was struck for four.

Nourse was resolute at the other end. Determined to stick to the very end. Sherwell in fact was a tad aggressive. The score started moving along too fast for English comfort.

Relf and Hayes were replaced, Lees and Crawford brought on. The batsmen played them with ease. Boundaries were struck. The score moved through the 240s, faster through the 250s.

A tiring Lees was taken off again, and Relf reintroduced. Nourse drove firmly and freely. His half cut half drive behind point was an effective and elegant stroke. He was also strong on the leg side, while excellent in back play. Sherwell negotiated the bowling with aplomb, calm and cool to the very end.

The score progressed through the 260s, and now stood on 276. Eight more were needed. Crawford was bowling medium-pace with Relf and Hayes in the slips. The ball moved away outside off. Sherwell played at it. It took the edge and flew between Hayes and Relf for four. Groans all around the ground from English fielders. Warner was hovering around, trying to keep everyone calm. The crowd yelled hoarsely at the lucky break. 280 for 9. Nourse was on 90, Sherwell 18. The stand worth 41. Four more required.

Relf started a new over to Nourse. It was on the leg stump and the left-hander drove hard through the mid-wicket. It beat the ring of fielders and traveled along the quick outfield. The batsmen sprinted, turned, sprinted again, and as the ball was retrieved and thrown, ran back for the third. The scores were level. South Africa could not lose. The crowd was ecstatic.

Sherwell was on strike. Warner signaled his men to come in, form a ring around the batsmen. Relf was a seasoned pro, he surely knew what to do.

The second ball of the over. Perfectly pitched, and played with a dead bat.

Relf turned. Sherwell was ready. The third ball. Again the length and line perfect. The push went straight to the fielder.

The fourth ball of the over. Nails were being bitten around the ground. The ball was outside the off-stump, inviting a flirtatious stroke. Sherwell left it well alone.

Three dot balls.

Relf turned again. And now he bowled that ball. Slowest and easiest of full pitches ever bowled, that too on the leg-side. Warner wrote, “Relf! Relf! What were you about that at the crisis you should have presented Sherwell with (that). You who had up till then bowled with so much determination and life and with such accuracy of length?”

Sherwell heaved it to the square-leg boundary. “That slow full pitch was the one blot on a superb day’s cricket,” wrote Warner. “It was so tame and flat after all the strenuous exertion.”

South Africa had won, for the first time in their history of Test cricket.

What followed?

Let Warner take up the tale:

“Never have I witnessed anything like the scene at the finish. Men were shrieking hysterically, some were even crying, and hats and sticks were flying everywhere. When the winning hit had been made the crowd simply flung themselves at Nourse and Sherwell and carried them into the pavilion, while, for half an hour after it was all over, thousands lingered on, and the whole of the South African Eleven had to come forward on to the balcony of the committee room.”

After a while the great financier Abe Bailey came into the English dressing room and asked Warner to say a few words to the crowd. And the gracious captain said that he had never seen a side fight a getter rear-guard action.

“Defeat in such a struggle was glorious, for the first Test match will be talked of in South Africa as long as cricket is played there,” Warner concluded.

He was underestimating the restrictions of recency effect and generation-orientation, though. Sadly, the generation that witnessed the game is no longer with us and very few remember that splendid Test match today. Very few even recall that leg-spin googly bowlers ever existed in South Africa. The greatness of Faulkner, of Schwarz, of Vogler, of White … or Nourse and Sherwell … all that is seldom recalled today.

However, a glance at the record books still tell us that it is one of the only 11 Tests to have been decided by the margin of one wicket. And then when we look at the scoreboard all these names suddenly reveal themselves, with so many bowling styles turning out to be leg-break googly.

Yes, there are endless delights of delving into the obscure scorebooks that document the game.

Brief Scores:

TRENDING NOW

England 184 (Jack Crawford 44; Reggie Schwarz 3 for 72) and 190 (Plum Warner 51, David Denton 34, Jack Crawford 43; Aubrey Faulkner 4 for 26) lost to South Africa 91 (Walter Lees 5 for 34, Colin Blythe 3 for 33) and 287 for 9 (William Shalders 38, Gordon White 81, Dave Nourse 93*, Percy Sherwell 22*; Walter Lees 3 for 74) by 1 wicket.