This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

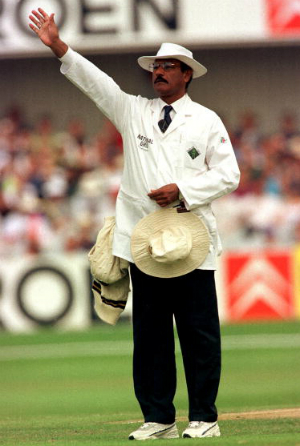

Javed Akhtar: Brilliant with ball, controversial in white coat

It is a pity Javed Akhtar is remembered for all the wrong reasons.

Written by Abhishek Mukherjee

Published: Nov 21, 2015, 07:30 AM (IST)

Edited: Jul 08, 2016, 05:00 PM (IST)

Javed Akhtar, born November 21, 1940, had a dignified career that fetched him 187 wickets at a shade above 18. Unfortunately, he played a solitary Test, that too being a surprise pick, and was discarded somewhat harshly. He ended his career amidst controversies that involved being accusations of match-fixing and retaliation in the form of a lawsuit. Abhishek Mukherjee tells the tale of the Pakistani champion that never happened.

Google Javed Akhtar, and you will come across the lyricist and one-half of Bollywood’s most iconic screenplay-writer duo. You cannot blame Google. Few will guess you are looking for the Rawalpindi off-spinner who toiled hard for over a decade with his off-breaks (who eventually became the umpire Google thought).

But Akhtar was special, for his 187 wickets from 51 matches came at a mere 18.21. Standing at about six feet, Akhtar bowled to a flat trajectory, keeping things quiet, and yet managing to take wickets at regular intervals. He took a wicket every 48.9 balls, which is remarkably good for an off-spinner. To put things into perspective, Jim Laker had an average of 18.41 and a strike rate of 52.1.

Akhtar lost out to the all-rounders, Mushtaq Mohammad and Intikhab Alam, and that near-forgotten wily genius Pervez Sajjad. There was also Mohammad Nazir, but Akhtar should ideally have got a longer run. His solitary Test, after all, was a surprise call-up of sorts, which did not give him a chance to get accustomed to the conditions.

Early days

Born in Delhi in 1940, Akhtar moved to Pakistan during the turbulent days of the Partition. The Akhtars settled down in Rawalpindi, and Javed took to cricket almost immediately. He first played serious cricket in 1959-60, taking 4 for 31 against Combined Services. In his second match, against the same team, his figures read 6 for 21 and 4 for 23. He had arrived.

Ted Dexter’s MCC toured Pakistan in 1961-62, and Akhtar was included in the match for President’s XI. The Englishmen were left clueless against him: he claimed 7 for 56 in the first innings, three of which were bowled. Among others, the wickets included those of Dexter, Ken Barrington, Eric Russell, Peter Parfitt, and Bob Barber.

By this time there was no question about his pedigree. At this point his career tally read 65 wickets at 14.60 from 13 matches. A selection for the England tour of 1962 was inevitable.

Test cricket

The tour started with the customary match against Duke of Norfolk’s XI at Arundel on April 28, 1962. The third Test at Headingley started on July 5, 1962. Pakistan played 19 matches in these 68 days. Exactly why Akhtar did not play a single match during this phase remains a mystery to mankind, but it remains a fact that he was thrown to the lions straight into the Headingley Test.

Wisden was sympathetic: “Akhtar had the unique experience of bowling his first ball on arrival in England in this Test so there was every excuse for him not producing his true form, although with his fine build and brand new flannels and boots he looked the part.”

England thrashed Pakistan in the first two Tests at Edgbaston (innings and 24 runs) and Lord’s (9 wickets). They decided to make three changes to the team: Imtiaz Ahmed, Antao D’Souza, and Wallis Mathias made way for Munir Malik, Ijaz Butt, and Akhtar, who was the only debutant of the Test.

Javed Burki put England in, for as Wisden wrote, the conditions included “a leaden sky, heavy atmosphere and a green pitch were ideal for the seam bowlers.” In the process Burki became the first Pakistan captain to win the toss and field first outside Pakistan; he would do the same in the following Test.

Micky Stewart scored a solid 86, but England were still reduced to 180 for 6 when Parfitt took control. The last four men — John Murray (29), David Allen (62), Fred Trueman (20), and Brian Statham (26*) — all came good. Parfitt added 67 with Murray and 99 with Allen before falling for 119.

But Akhtar had his chance: at 102 Parfitt hit one to cover off him, but Mahmood Hussain dropped him. In the end he finished with 16-5-52-0 as England managed to pile up 428.

The rest passed in a blur. Alimuddin scored 50 and 60, Saeed Ahmed 54 in the second innings, but Pakistan were blown away for 131 and 180 with every bowler chipping in. England went up 3-0, and eventually claimed the series 4-0 after rain saved them at Trent Bridge.

Thankfully, Akhtar was got to play tour matches thereafter. To be fair, he did not exactly take The Mother Country by storm. He had match figures of 3 for 49 against Lancashire and 4 for 100 against Hampshire, but that was about it. His 10 wickets came at 37.90.

Back home…

Back to the comforts of familiar conditions, Akhtar roared back into form. He played from 1959-60 to 1971-72, and barring that England tour his worst average for a single season was 27.25. In fact, till 1964-65 his First-Class numbers (barring the England tour) read 101 wickets at an astonishing 14.66.

It seems almost unreal that he was not picked again, especially at home — more so because Pakistan won only one series out of seven during this phase, that too against New Zealand at home.

As his career petered out, Akhtar concentrated on batting. His batting had peaked for a while in 1964-65, when he scored 65 and 88 in consecutive innings. He eventually finished with 835 runs at 15.75 with 5 fifties.

Donning the white coat

With time running out, Akhtar turned to umpiring. By 1973-74 he was standing in Quaid-e-Azam Trophy matches. He made a comeback as player in the BCCP Patron’s Trophy 1975-76, taking 3 for 19 for Rawalpindi against Servis Industries. Less than two weeks later he stood as umpire in the quarter-final between Pakistan International Airlines and Sargodha.

The opportunity to stand in an ODI came in 1976-77, in a match between Pakistan and New Zealand at Sialkot. He was also one of the umpires in the ill-fated ODI at Sahiwal, where Bishan Bedi conceded the match after Sarfraz Nawaz kept bowling bouncers beyond the reach of batsmen.

The following season he stood in a Test at Faisalabad, against Australia, and eventually stood in 18 Tests and 40 ODIs. In 1986 he wrote an Urdu book, the title of which translated to Laws of Cricket.

He was in the panel for the 1997 Independence Cup in India — the first time he officiated in an international match outside Pakistan. He was inducted into the ICC Panel, and stood in a Test between South Africa and Sri Lanka at Centurion in 1997-98.

Then came the Headingley Test of 1998.

Man of law files lawsuit

The Test deserves a background. Thanks to a 10-wicket victory in the second Test at Lord’s, South Africa led 1-0 after 3 of the 5 Tests were played. England hit back at Trent Bridge, winning by 8 wickets (this was the Test where Michael Atherton scored 98 not out) to square the series.

The fifth Test was keenly contested, and was one of the epic contests of the decade. Mark Butcher’s 116 took England to 230 as Allan Donald, Shaun Pollock, and Makhaya Ntini shared the wickets. South Africa secured a 22-run lead; this time Darren Gough, Angus Fraser, and Dominic Cork took all 10.

Donald and Pollock both took five-fors, but a dour 7-hour 94 from Nasser Hussain helped England set 219. Gough reduced South Africa to 27 for 5; Jonty Rhodes and Brian McMillan added 117 for the sixth wicket; and in the end England won the cliff-hanger by 23 runs to clinch the series. READ: 12 classic England-South Africa Tests

It was an intense contest marred by below-par umpiring. It must be remembered here that South African moods were already on a low: Donald had been fined 50 per cent of his match fee for complaining against Mervyn Kitchen’s decisions at Trent Bridge on air. In fact, match-referee Ahmed Ebrahim had made up his mind to ban Donald, only to change his mind at last moment.

Substandard umpiring is not new to cricket. David Shepherd and Eddie Nicholls put up an equally terrible show at Old Trafford, 2001. Chasing 370, England were bowled out for 261 against Pakistan. Shepherd actually considered retirement after the Test, but was convinced not to.

More recently, Steve Bucknor and Mark Benson (both neutral umpires) were reprimanded after several shocking decisions against India at SCG. There was MV Nagendra, who apologised to Mike Brearley: “I knew it was not out, but I felt my finger going up and I just couldn’t stop it.” There was Bapu Joshi, who brought the Bombay cliff-hanger between India and West Indies to a bizarrely premature end. One can go on.

Akhtar, to be fair, was terrible during the Headingley Test. Wisden shunned him, calling his performance “four days of painful notoriety.” Unfortunately, incompetence would not be the only allegation he would be up against.

Akhtar stood in another Test, against Australia at Rawalpindi, before going on to officiate in the 1999 World Cup. He did not stand as umpire in international cricket after that. He quit after that following poor health.

In 2000, match-fixing allegations were raised against Akhtar, mainly by Ali Bacher. He told King Commission: “That Test match was won by England, but there were a lot of dubious decisions given. There were 10 lbws, nine of them given by Pakistani umpire Javed Akhtar, and eight of them went against South Africa.” The Telegraph added that Bacher claimed Akhtar was “on the payroll of a Pakistani bookmaker.”

Interestingly, Bacher did not utter a word against Kitchen, who was English. This, despite England won both Tests, and it was more likely that the home umpire would make biased decisions instead of his neutral counterpart.

In an interview with Imtiaz Sipra for ESPNCricinfo, Akhtar lambasted Bacher, calling the allegations “absurd, rubbish, and totally devoid of truth.” He added: “Never ever in my umpiring career, financial or other temptations have affected my decisions. It was more due a human error than anything else.”

He also told BBC: “I curse such filthy money. No one dared to contact me with such intentions like match fixing or any other malpractice. Whatever I have earned is through umpiring and now from the income of my whole life I will try to make my own house.”

Akhtar eventually sued Bacher for PKR 100 million (R 14.8 million, approximately, at that time). The judge of the case, scheduled for November 27, 2000, was also called Javed Akhtar. Cricketer-turned-umpire Javed Akhtar was represented by Advocates Waqar Siddique Loan, Tahir Jameel Butt, and Tariq Pervez Abbasi.

However, Bacher refused to appear: “My evidence before the King commission was given as a result of my Board and the South African government urging me to disclose any information known to me concerning match-fixing and corruption in cricket. I believe that I have openly and honestly testified and trust that this evidence will assist in some way to stamp out corruption in cricket. I do not intend to be drawn into litigation in Pakistan, particularly in view of the fact that I have been advised that the Pakistan court does not have jurisdiction in this matter.”

Akhtar was subsequently cleared by the Bhandari Commission in 2002: “”As regards to the conduct of umpire Javed Akhtar, there is hardly any material or even a suggestion or inference that umpire Javed Akhtar by design gave large number of lbws. In all fairness, as the South African board initiated and inspired allegations against Javed Akhtar, it ought to have come forward to assist the Commission in resolving the matter. In spite of a number of letters, the South African Board did not respond nor send any material for consideration by this Commission.”

He passed away on July 8, 2016. He was 75.

(Abhishek Mukherjee is the Chief Editor at CricketCountry and CricLife. He blogs here and can be followed on Twitter here.)