This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Kennington Oval, a brief history: Part 3

The bare bones of the 1882 Oval Test may be expressed as Test # 9, England v Australia. Australia had won by 7 runs. But, and there is a big ‘but’ in all this, making the bland statement above is akin to stating that Pandit Ravi Shankar was an itinerant strummer or that Michelangelo was a hewer of stone.

Written by Pradip Dhole

Published: Nov 06, 2017, 11:47 AM (IST)

Edited: Nov 06, 2017, 11:47 AM (IST)

“Sing in me, Muse, and through me tell the story

of that man skilled in all ways of contending…”

— The Odyssey, Homer

It was a fairly buoyant English side (England having won the one-off Oval Test of 1880 by 5 wickets) under Alfred Shaw that arrived at ASN Company’s wharf, Sydney, via North America, on the Australia’s on Wednesday, November 16, 1881 at about 5 PM. They were greeted by JM Gibson, Honorary Secretary of New South Wales Cricket Association, who escorted them to the Oxford Hotel where the team was to be put up.

The squad comprised only 11 players, out of whom six players had never played Test cricket before. Of the remaining, Shaw of Nottinghamshire and the two Yorkshiremen (Tom Emmett and George Ulyett), had played 3 Tests each. Another Nottinghamshire man, John Selby, had played 2 Tests previously. Interestingly, Billy Midwinter, who had played 2 Tests for Australia previously, was about to turn out for England on this trip and to become the first cricketer to represent two different countries in Test cricket. James Lillywhite Jr, manager of the team, had played in the first 2 Test matches of all. Having fallen ill before the departure of the team, Arthur Shrewsbury was scheduled to arrive the following week. Interestingly, out of the present squad, skipper Shaw was the only one who had played in that Oval Test of 1880.

The team played 18 matches in Australia of which only 7 were accorded First-Class status; these included 2 matches against Victoria, 1 against NSW, and 2 Tests each at Sydney and Melbourne. Shaw’s XI won all three regional matches by substantial margins. The first Test at Melbourne was drawn. Australia got the better of the visitors by 5 wickets in the second Test played at Sydney. England won the third Test, also played at Sydney, by 6 wickets, while the fourth Test, played at Melbourne, was drawn.

The tourists left Adelaide on the Orient Line steamship Chimborazo on March 24 in a somewhat subdued state of mind. However, the £700 profit from the composite tour may have given some solace to the returning cricketers.

The memory of the on-field fracas (and physical manhandling of some of the English players, including Lord Harris himself) surrounding the tour match against NSW at Sydney during the 1878-79 tour was still very much in the minds of the powers that be in England. In addition, the fact that Lord Harris had been severely displeased by the fact that the Australian players, nominally ‘amateurs’ like the majority of his own team, were being paid relatively larger sums of money as match appearance fees, had led to him refusing to play another Test at Sydney and leaving Australia with his team prematurely and very much under a cloud of discontent.

Placating the English cricket hierarchy prior to a projected Australia tour of England in 1882, therefore, was not going be an easy task. It was left to Charles William Beal, lawyer, Secretary of Carlton Club, and Honorary Secretary of the NSWCA, to pen a well-thought-out and precisely worded letter to Henry Perkins, Secretary of MCC and English agent for Melbourne CC, the prime movers for sending Australian teams to England on cricketing tours.

There were two major issues to be addressed in the letter. The first was to convince the English cricket authorities that NSWCA were equally interested in the projected tour and were willing to extend their blessings for the venture. The second was a little more sensitive. It was important to impress upon the English cricket establishment that the Australian cricketers about to undertake the tour were truly amateurs in status in the strictest sense of the term.

The persuasive style of Beal seems to have dispelled the misgivings in the English camp and they gave their concurrence for the tour quite willingly. Perkins was given a free hand as far making the local arrangements for the tour were concerned and a full programme for cricket fixtures was soon made possible.

The crucial business of selecting the team was entrusted to the tried and trusted pair of Billy Murdoch and Harry Boyle. Some of the members were almost automatic choices, given their previous Test experience. ‘Black’ Jack Blackham, having played in each of the first 8 Tests, would probably have been the first choice. Murdoch (7 Tests) would not have been far behind. Boyle (6), Tom Garrett (6), Tom Horan (6), Alec Bannerman (5), Percy McDonnell (5), ‘Joey’ Palmer (5), all veterans of Test cricket by the time, were soon on the team sheet. Sammy Jones (destined to play a very crucial, if unwitting, role in his third Test), and the gentle giant, the 6’ 6” all-rounder, George Bonnor, having played 1 Test previously, were penned in in due course. The 4-Test veteran Hugh Massie, employed at a Bank, was graciously allowed time off and was added to the squad. Fred Spofforth (2 Tests) finally made himself available, to the relief of all, and the South Australia stalwart George Giffen (3 Tests) completed the list of the 13-man touring party.

After a grand send-off banquet at Campagnoni’s rooms in honour of Beal, designated manager of the touring team, the tourists were seen off on Thursday, March 16 from Williamstown Railway Pier, Melbourne, on the RMS steamer Assam, barely two days after the conclusion of the fourth Test of 1881-82 series. There was one other illustrious passenger on the same vessel on the voyage in Charles Bannerman, though he was not with the touring Australian team.

Simon Burnton, writing in The Guardian, relates an intriguing story concerning Bonnor while on the voyage over to England. His striking figure made Bonnor, once described as “a giant of strength and an Apollo of grace” and widely known as “The Australian Hercules”, quite a popular draw on board. It seems that one misguided person had thought it fit to wager £100 that Bonnor would not be able to throw a cricket ball 110 yards without a proper warm-up. Well, on arrival at Plymouth on May 3, Bonnor and the rest of the party decided to settle the issue at the nearby Raglan Barracks. It is said that Bonnor had hurled the ball a distance of 119.5 yards from a standing start, thus earning himself a bonus of £100 (more than £10,500 in this day and age) almost immediately on alighting from the boat, perhaps a happy omen of things to come on the tour.

The first of the cricket fixtures of the tour began on May 15 against Oxford. Massie made an immediate impact on the game with an innings of 206 in a total of 362, The Australians won easily by 9 wickets. Murdoch played himself into fine early form with a humongous 286 against Sussex at Hove.

These were to be the only double centuries by the Australians on the tour. The tour involved a total of 39 matches, 33 of which were of First-Class status, including the one-off Test match. There were a total of 5 matches played at The Oval during the course of the tour.

Australia won the first of these games, against Surrey by 6 wickets, even though they were 70 runs in arrears on the first innings. Superlative bowling by Boyle (7 for 52 and 4 for 16) was instrumental in powering the visitors to victory. Garrett (6 for 30) joined hands with Boyle to dismiss the home team for only 48 in the second innings.

In the second match, against The Gentlemen, Giffen starred with both bat and ball. The visitors won by an innings and 1 run as Giffen scored 43 and claimed 8 for 49 and 3 for 60.

Against the Players, however, the boot was on the other foot. The tourists went down by an innings and 34 runs. The batting heroes for the Players were Maurice Read (130) and Billy Barnes (87). The last encounter at The Oval was the drawn game between the visitors and an Alfred Shaw’s XI, Spofforth and Ted Peate taking 6-wickets hauls in an innings in the game.

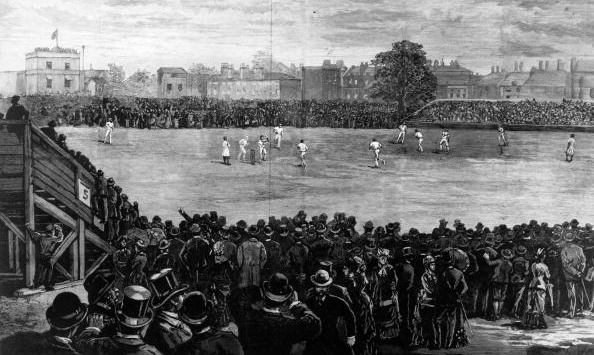

The above, then, were the First-Class games played at The Oval on the tour. There was, however, one more match played at the venue, the only Test match of the tour.

The bare bones of the match may be expressed as follows: Test # 9, England v Australia at Kennington Oval, played on August 28 and 29, 1882 with 4-ball overs. For the record, Australia had won the match by 7 runs. But, and there is a big ‘but’ in all this, making the bland statement above is akin to stating that Pandit Ravi Shankar was an itinerant strummer or that Michelangelo was a hewer of stone.

Mention of the above Test match takes one’s mind back to the forenoon of a warm summer day about five years ago when the chronicler was on a visit to the Sports Museum at MCG. Browsing through the various exhibits covering a wide range of sporting activity, the chronicler noticed a group of schoolchildren in one area of the Museum being spoken to by a lady who appeared to be an employee of the Museum. Eventually arriving in the close vicinity of the group, it transpired that the lady was pointing to a replica of the famous urn on one of the shelves and telling the wide-eyed children the story of the fascinating Test that had spawned the legend of the Ashes.

Glancing around, an exhibit of an unusual shape on an adjoining cabinet caught the eye. It turned out to be a sculpture of an upturned hand with the open palm facing upward made of some metallic material, preserved in a glass case. Closer scrutiny revealed a blackish round object placed on the upturned palm. On approaching the exhibit for a closer look, the chronicler noticed a card inside the glass case. The legend stated that this was the very ball used for the famous Oval Test of 1882, now, sadly, blackened with age. It seems that following the sensational conclusion of the Test, and while everyone had been in a highly excited state, Blackham, by now the veteran of 9 Tests, had noticed the match ball lying around unattended close to the pitch and had had the foresight to put it in his pocket.

With so much going on, no one had enquired about the whereabouts of the ball. Blackham had ultimately taken it home and shut it up in one of his drawers with a brief note about its provenance. Years after Blackham’s death, his wife had discovered the treasure and the note while cleaning out the drawer. She had immediately realised the historical significance of both the object and the note and had, thankfully, turned them over to VCA. They, in turn, had thought it proper to donate it to the Museum. The reader can well imagine the welter of emotions jostling about in the chronicler’s mind as he stood there beholding the wondrous ball that had won Australia that historic game.

Murdoch won the toss under somewhat uncertain weather conditions. Bannerman and Massie made their way to the wicket at about midday. In hindsight, and as the day unfolded, Murdoch would probably have felt that his decision may not have been beneficial for his team. Massie (1) was back in the pavilion with only 6 on the board, bowled by a yorker on the leg-stump. Murdoch was the next to depart, playing on to Peate, but not before he had scored 13 from 50 minutes’ occupation of the crease. The total read 21 for 2 at that point. Bonnor (1) was next out, clean bowled, middle stump, with the total reading 22 for 3 in 39.2 overs, and things not looking very promising for Australia.

The quintessential stonewaller, Bannerman (9) was fourth dismissed, at the total of 26, caught left handed by WG Grace, a low catch at point, having spent 70 minutes at the crease and having faced 86 deliveries. In keeping with his dour philosophy about batting, he did not feel inspired to hit any boundaries.

The fifth and sixth wickets both fell at 30 with the departures of Horan (3, bowled leg stump) and Giffen (2) respectively. The total limped along to 48 (in 69 overs) when the seventh wicket fell, Garrett (10) wending his philosophical way back to the pavilion.

Boyle’s innings (2) ended with the score at 53 for 8. Jack Blackham (17, the highest individual scorer in the innings) left at 59 after 6 more overs of sustained effort. It was all over when Jones was dismissed for a duck at the total of 63 at the conclusion of the 80th over. He left Spofforth undefeated on 4. It was a demoralising experience for Australia, 63 being the lowest innings total in Test cricket at the time, not a record to be proud of. The Guardian considered the first day “the most considerable disaster of their visit”. They occupied about 2 hours of laboured batting on a greenish wicket which afforded the English bowlers considerable assistance.

Dick Barlow had the best bowling figures (31-22-19-5) for England while Peate, the leader of the attack, returned figures of 38-24-31-4. George ‘Happy Jack’ Ulyett (so named because of his habit of whistling merrily on the field), opened bowling along with Peate and took the other wicket.

England skipper ‘Monkey’ Hornby then sent Barlow and Grace in to open, at about 3:30 with the light failing rapidly. Playing an unduly subdued hand, WG (4) was the first man dismissed, at the total of 13. Five runs and 5 overs later, Barlow (11) was on his way back. ‘Bunny’ Lucas came in to join Ulyett, and the duo put on a stand of 39 runs in 25.2 overs, with Ulyett by far the more dominant partner.

The partnership ended when Ulyett, while jumping out to play Spofforth, was stumped by Blackham for 26 (the highest score for England). At this point, Spofforth had taken all the wickets to have fallen. The fourth wicket fell at 59, and things went rapidly downhill for England from that point onwards, with wickets tumbling at disconcertingly frequent intervals.

Even The Guardian was moved to comment, in the measured manner so characteristic of the paper, that: “The change that had come over the game was a keen disappointment to the spectators, who were very quiet as the English batsmen went down one by one before the Colonists’’ splendid bowling.” Lucas batted for all of 65 minutes for his dogged 9. Debutant CT Studd failed to trouble the scorers (an expression disliked intensely by the late Bill Frindall, the doyen of English cricket statisticians).

When wicketkeeper Alfred Lyttelton (2) made his slow way back, the total read 63 for 6. This Lyttelton was barely 25 years old at the time, but was already a Member of Parliament on a Liberal Unionist ticket, and had represented England at football against Scotland in the previous year, even being among the goal scorers. The fall of the wicket brought Barnes to the wicket, another man blessed with a sunny disposition, but with the reputation for being fondof a convivial bottle or two, or three, if the opportunity presented itself.

There is a story of Barnes once arriving at Lord’s late and in a state of moderate inebriation for a match against Middlesex and, even in his slightly befuddled state, scoring a century before lunch. When reprimanded by his Nottinghamshire committee for his twin misdemeanours, he is reported to have told the Committee: “Beggin’ your lordships’ pardons, if ah can go down to Lord’s and get drunk and mek a century ’fore lunch, then ah thinks it ud pay t’Notts committee to get me drunk afore every match.” Well, his earthy charm did not work this time, and he was soon back having contributed 5.

From the fall of the third wicket till this point, then, England had lost 5 for 13. There was an air of disquiet in the English dressing-room.

At the other end, England’s other debutant Read was feeling his cautious way around the attack and bearing his soul in patience and fortitude. AG Steel, the next man in, took his courage in both hands and scored 14 before he pulled a ball from Garrett on to his stumps, leaving the total 96 for 8. Hornby was bowled by Spofforth for 2.

The innings ended 2 deliveries later when Peate was caught by Boyle off Spofforth for a duck. The innings ending at 101 in 71.3 overs, giving the home team a vital -run advantage, a considerable bonus at this stage of the match. For Australia, the bowling of Spofforth (36.3-18-46-7) was the outstanding feature of their cricket so far in the game. Four of Spoforth’s 7 victims were bowled. The first day’s play ended with the termination of the England innings.

The start of the second day’s play was a little delayed, at about 12.10. Taking his courage in both hands, the 28-year-old Massie launched the Australian second innings in cavalier fashion, quite against the run of play in the game so far, and the Australian 50 was raised in 36 minutes off 20.1 four-ball overs. Having scored a rapid 55 (off 62 deliveries with 9 fours and with a let-off on his score on 38 when Lucas had grassed a chance at long-off from the bowling of Barnes), easily the highest individual score of the match, Massie departed, bowled leg-stump by Steel, at the team score of 66 after the deficit had been wiped off at about 12.45.

Australia’s next 2 wickets both fell on the team score of 70 when first Bonnor (2), then Bannerman (13 in 70 watchful minutes at the crease) made their respective ways back to the pavilion. The fourth and fifth wickets both fell at 79 with Horan (2) and Giffen (a first ball duck) both being summarily dismissed. At this point, Australia wereonly 41 runs ahead, having lost half the side. Blackham (7) was the next to depart, and the score read 99 for 6. There was some rain when the total reached 99 and lunch was taken early.

The post-lunch session began at about 2.45 after more scattered showers. In the meanwhile, Murdoch had been playing a watchful hand and holding the fort for Australia. He was joined by the 21-year-old Jones.. Realising the gravity of the situation, Jones played a cautious innings, giving his skipper as much support as he could. The total crept steadily up to 114 when the first turning point of the Test match occurred.

WG was bowling his famous ‘donkey drops’. Jones played a delivery to point and took off for a single. Having popped his bat behind the batting crease, Jones ventured out of his ground to pat down a portion of the pitch, with no intention of taking a run, not realising the ball was not dead at that point. The ball having been thrown in to ‘keeper in the meanwhile, Lyttelton suddenly noticed Jones out of his crease and threw the ball to WG who whipped off the bails at the bowler’s end, and appealed for a run out. The ball still being in play technically, Bob Thoms, one of the most respected umpires of the day, upheld the appeal and sent the bemused but wiser Jones (6) on his way back. Australia were now 114 for 7.

The next man in was Spofforth, not one to mask his feelings with a veneer of genteel inscrutability. According to John Miller in The Ashes: Cricket’s Greatest Contest, the conversation between the excitable Spofforth and skipper Murdoch went something like this:

Spofforth: What do you think of what happened to young Jones?

Murdoch: It wasn’t the most courteous piece of sportsmanship I’ve seen, Fred.

Spofforth: I swear to you, England will not win this.

His mind throbbing with righteous indignation at the seemingly unsportsmanlike behaviour of Grace, the highly incensed Spofforth was dismissed for a 5-ball duck, leaving Australia at 117 for 8. It became 122 for 9 soon when Murdoch (29) was run out through the joint efforts of Hornby, Studd and Lyttelton. Within a bare 10 minutes of the controversial dismissal of Jones, the Australian innings was completed with the dismissal of Boyle for a first-ball duck. England now had a winning target of a mere 85 runs. It was now 3.25 on the second afternoon of the Test.

As can be readily imagined, there were tumultuous scenes in the Australian dressing room during the interval between innings, and much gnashing of teeth at the apparent ‘injustice’ of the Jones dismissal. In an effort to arouse the fighting spirits of his teammates, Spofforth is reported to have roared: “This thing can be done!” The Australians took the field for the final innings of the match with Spofforth’s war cry still ringing in their ears, and play resumed at 3.45.

The Guardian had opined: “When the England innings opened with only 85 runs to win, nothing seemed more certain than that the Colonials would suffer a crushing defeat.” The first two English wickets both fell on 15, Spofforth bowling Hornby for 9 (hitting his off-stump) and his Lancashire mate Barlow (0) with successive deliveries.

Ulyett, the Yorkshire professional, then joined Grace at the wicket. Runs came at a relatively easy pace for a while and the England 50 was raised in 43 minutes, off 21.3 overs. Just when English fans were beginning to feel a sense of reassurance at the solidity of the partnership between the Champion and the hardened professional, there was another twist in the tale.

Ulyett (11) was third man out, caught behind by the prowling Blackham off Spofforth, the wicket falling at 51. The third-wicket stand had realised 36. It was to be the most fruitful collaboration in the innings. In the guarded words of The Guardian: “After the stand made by Mr Grace and Ulyett, the betting was at enormous odds. The crowd, numbering upwards of 20,000 persons, was wrought up to a pitch of intense excitement and every hit was enthusiastically cheered. The Australians, however, never bated a jot of hope and courage.”

Grace (32) fell at 53. England needed 35 runs for a victory at this point with 6 wickets in hand. Lucas and Lyttelton played cautiously and the total gradually crept up to 66 for 4. Perhaps the expectations, both of the fans and of the teammates, bore down too heavily on the minds of the batsmen at the crease at this time: they proceeded to play out 12 successive maiden. The tension around the ground mounted almost palpably with every delivery ‘wasted’. Australia conceded a single at this point (deliberately, according to some), but four more maiden overs followed.

When Spofforth bowled Lyttelton (12), the total read 66 for 5 in 49.2 overs, England needed another 19 to win. The fifth-wicket pair had batted out almost 25 overs. “Still, with 19 runs to win and only half the wickets down everything seemed favourable to England,” said The Guardian. “But the Colonists, whose play cannot be too much praised, had totally demoralised their opponents.”

This was to be the second, and more significant, turning point of the game. According to Horan, the strain was all-pervading: “The strain, even for the spectators, was so severe that one onlooker dropped down dead, and another with his teeth gnawed pieces out of the top of his umbrella. For the final half-hour you could have heard a pin drop. That was the match in which the last English batsmen had to screw his courage to the sticking place by the aid of champagne, when one man’s lips were ashen grey, and his throat so parched that he could hardly speak as he strode by me to the crease. That was a match worth playing in, and I doubt whether there will ever be such another game for prolonged and terribly trying tension.”

Steel strode to the wicket at No. 7, played nervously at the first 2 deliveries he faced from Spofforth, and was caught and bowled off the third ball he faced for a duck. For all his first-innings resolve at the wicket, new man Read was bowled by Spofforth for a 2-ball duck.

England were suddenly 70 for 7, with 15 runs still to get for a win. Normally paragons of icy calmness about their prose at all times, The Guardian reported: “With his [Read’s] dismissal a change came over the scene. Whilst the Colonists could not help betraying their glee, the spectators became downcast and silent.”

England lost their eighth wicket at 75 when the patient Lucas (5 in 65 minutes of vigilance) played on to his stumps to become Spofforth’s 14th victim of the Test. The “moving finger” had by now put the writing firmly on the wall for England, with 10 more runs to get, only two men left to get them, and the opponents with their ‘Colonial’ tails well and truly up.

This may be an appropriate point in the narrative to provide some details about Spofforth’s performance in this Test so far: his last 11 overs had cost him just 2 runs and had earned him 4 wickets, including a sequence of 3 wickets in 4 balls, this being the first instance of this particular feat in Test history. The magnificent performance was to inspire Giffen to write: “irresistible as an avalanche,” and “the finest piece of bowling I have ever seen.”

It was, however, Boyle who finished off the Test with the wickets of Barnes (2), caught off his glove and Peate (2). The last wicket fell at 77. The entire innings lasted 116 minutes. Spofforth returned figures of 7 for 44 to complement his first-innings effort 7 for 46, to claim match figures of 14 for 90.This was the first time in Test history that any bowler had claimed 14 wickets in a match.

And on a chilly, damp August afternoon, at The Oval, Australia emerged as winners of the riveting contest by a slender margin of 7 runs, “a fitting reward for their superb bowling and fielding and their remarkable pluck,” in the summation by The Guardian. Wisden, however, was more grudging in its summary of events, leaving the reader to: “attribute the Australian victory to the fact that the Colonists won the toss and thereby had the best of the cricket; to the fact that the English had to play the last innings; to the brilliant batting of Massie; to the superb bowling of Spofforth; to the nervousness of some of the England side; to the glorious uncertainty of the noble game; or to whatever he or she thinks the true reason.”

It took a little time for the reality of the events to sink in. When it did, Spofforth, the undisputed hero of the epic Test, was carried shoulder-high back to the dressing room by his ecstatic teammates. There had never been, of course, any shred of doubt whatsoever in anybody’s mind regarding the bowling capabilities of Spofforth, particularly in English conditions.

Spofforth had established his credentials emphatically on the 1878 tour of England, specifically, in the match against the MCC at Lord’s on 27 May, when the game had ended in a day, Spofforth claiming figures of 5.3-3-4-6 and 9-2-16-4. In that remarkable game, a batsman had arrived at the batting crease 37 times, but had been able to reach double figures on only thrice in the entire match.

The MCC team for the match, arguably a full-strength England team, had slipped from the relative comfort of 27 for 2 to the abyss of being 33, and Spofforth had claimed 6 of the wickets in the carnage, including a hat-trick, at a personal cost of only 4 runs. It is said that Spofforth had run around the Australian dressing room after the match repeatedly asking the rhetorical question, “Ain’t I a demon? Ain’t I a demon?” It is thus believed that the appellation of the “Demon” had been largely self-attributed.

Over the years, members of the cricket fraternity and the media have thought it fit to heap encomia on Spofforth’s dark-haired head. Grace had been quoted as saying: “His pace was terrifically fast, at times his length excellent, and his breakbacks were exceedingly deceptive. He controlled the ball with masterly skill and, if the wicket helped him ever so little, was almost unplayable. A good many batsmen funked [sic] Spofforth’s bowling and a great many found it impossible to score off him.”

John Trumble, brother of the more illustrious Hugh and a Test cricketer himself, had this to say about Spofforth: “He had a different grip of the ball for each of the three paces he bowled, and it must have necessitated for him very strenuous practice to secure accuracy with the grip he had for his very slow ball. But he could do many remarkable things with his hands, even throwing a new-laid egg a distance of 50 yards or so on turf and causing it to fall without breaking.”

The press were all in praise for his subtle variations of pace: “Spofforth varies his pace in the most remarkable way, at one time sending down a tremendously fast ball and at another almost a slow one.” Indeed, Spofforth is well-known to have been an avid advocate of variation of pace throughout his active cricket career.

Having recovered partially from the shock of the unexpected defeat in the Test match that ended on August 29, 1882, the local media began to give vent to their feelings in the characteristic self- deprecatory style so typical of the British. The Charles Alcock-edited Cricket: A Weekly Record of the Game carried the following (little remembered) dirge in its August 31, 1882 edition:

SACRED TO THE MEMORY

OF

ENGLAND’S SUPREMACY IN THE

CRICKET-FIELD

WHICH EXPIRED

ON THE 29TH DAY OF AUGUST, AT THE OVAL

—-

“ITS END WAS PEATE”

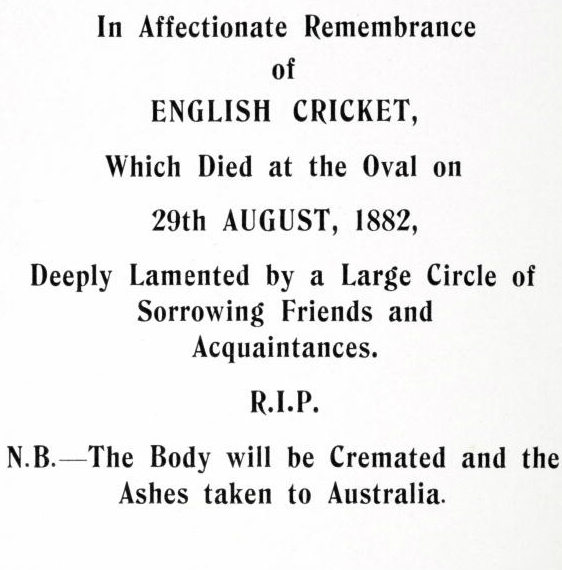

It was, however, this insertion in The Sporting Times on September 2, 1882 under the by-line “Bloobs” that really set tongues wagging:

Popularly believed to have spawned the legend of The Ashes, this happened to be the brainchild of journalist Reginald Shirley Brooks. There seems to have been a deeper connotation, however, to the insertion than the obvious reference to cricket in the mock obituary of The Sporting Times.

Mike Selvey had an intriguing story to tell in The Guardian under the title Ashes to ashes, dust to dust, if Shirley can’t further the cause his son must: “The origin of the urn owes more to a campaign for legalising cremation than a satirical lament for English cricket.”

The story of that obituary from the pen of Brooks, Selvey feels, may well have begun on January 13, 1874 at 35 Wimpole Street, where a meeting was being held in the residence of Sir Henry Thompson, one of the renowned surgeons of the day. The issue under consideration happened to be the right to human cremation, illegal in the British Isles at the time.

Among those present was Shirley Brooks, father of Reginald, and a journalist, playwright, and novelist in his own right, and a regular contributor to Punch, becoming its editor in 1870. Brooks also happened to be a passionate advocate for legislation to legalise human cremation. Host Thompson had recently published a well-received paper entitled The Treatment of the Body after Death in the Contemporary Review, and was himself a champion of the right to cremation. Among the other like-minded notables present at the meeting was the celebrated British author Anthony Trollope.

After much discussion over canapés, a proposal was put before the assembled company by Thompson. A Declaration was drawn up at the meeting, reading, in part: “We the undersigned disapprove the current custom of burying the dead, and we desire to substitute some mode which shall rapidly resolve the body into its component elements.”

The meeting led to the setting up of a Cremation Society of England. Brooks, however, did not see the ultimate outcome of the campaign. He passed away on February 23, 1874, and, ironically, being buried at Kensal Green. The issue did not die out with the senior Brooks, though.

On the other hand, the campaign gathered strength; more people joined the ranks; prototypes of furnaces were built; and animal carcasses were burnt to demonstrate the benefits of cremation to the public. Officialdom, however, was still not impressed enough to initiate any legislation on the issue. Parliament refused to enact a suitable Act to permit human cremation. Things came to a head in 1882 at about the time that the touring Australian team set foot in England.

A gentleman from Dorset by the name of Captain Hanham wrote to the Cremation Society of England requesting help in a private matter. It seems that two deceased members of the Captain’s family, now placed temporarily in a mausoleum, had, in their lifetimes, expressed the specific desire to be cremated upon their demise.

Since the Home Secretary had refused to sanction Hanham’s plea mentioned in anofficial communication to the authorities in this regard, he was soliciting the Society’s help in the matter. The Society’s hands were tied, so Hanham went ahead anyway, constructing his own furnace for the purpose and fulfilling the last wishes of his deceased relatives about two months later (without any prosecution, it may be noted).

Reginald Brooks saw a wonderful opportunity to further his late father’s cause with the issue of human cremation very much in focus. He went ahead with his mock obituary, making a point of mentioning the cremation part. As a postscript, it may be mentioned that human cremation did begin in a small scale in about three years’ time but was not really legalised till the turn of the century, two decades after the death of Shirley Brooks, one of the original champions of the cause.

Whatever may have been the motive behind the insertion of the notice in the popular journal, Brooks had undoubtedly fired the imagination of the British and Australian cricket fraternity alike, and The Ashes were soon to become the Holy Grail of cricket supremacy between the two old cricket rivals.

Indeed, even before the Australian tourists had begun their last First-Class fixture in England at Harrogate on September 23, another English tour of Australia was already under way, an English team embarking on September 14, under the captaincy of Ivo Bligh, with the avowed intention of “winning back The Ashes” from Australia.

It is almost impossible to move away from the topic of the epic Oval Test of 1882 without mention of an incident described by David Frith in Frith on Cricket. The Reliance World Cup Finals had just been played out between Australia and England at the historic Eden Gardens of Calcutta on November 8, 1987. Australia won the thrilling match by 7 runs, the same margin by which Australia had won thatOval Test of 1882.

TRENDING NOW

The Manager of the Australian World Cup team, Alan Crompton, had then been presented the ashes of a World Cup bail in a small urn by the Indian scribes Mudar Patherya and Barry O’Brien, in the hope that the urn would be adopted as the One-Day Ashes for future matches between England and Australia — sublime touch!