This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Lobsters in Cricket, Part 23: Palairet, Fry, Stoddart, MacLaren — a clutch of famous names, minor lob bowlers and incidents

A striking name in this curious list is that of Lionel Palairet — one of the most elegant batsmen of all time, a stylist to his core. David Foot, the greatest expert on Somerset cricket, called him ‘probably the most stylish batsman to play for the county.’

Written by Arunabha Sengupta

Published: Apr 17, 2017, 09:39 PM (IST)

Edited: Apr 17, 2017, 09:44 PM (IST)

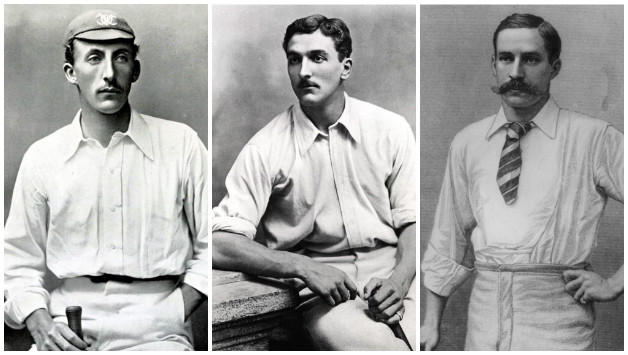

Before moving on to the magnificent swansong brought about by George ‘GHT’ Simpson-Hayward, Arunabha Sengupta looks at the turn of the 19th century and a clutch of minor lob bowlers who operated at that time, or turned to lobs because of some extenuating circumstances. The list included some famous names of cricket who distinguished themselves in other departments such as CB Fry, Lionel Palairet, Sammy Woods, Drewy Stoddart and others.

We have covered almost the entire stretch of the 19th century, with its clutch of lob bowlers; coming across some great names such as William Clarke, Walter Humphreys and Digby Jephson; and some minor ones such as EM Grace, WW Read and Teddy Wynyard. And soon we will encounter perhaps the greatest of them all, George Simpson-Hayward, the only specialist lob bowler to achieve success in Test cricket.

However, before we touch upon the incredible story of Simpson-Hayward, it makes sense to dwell on some of the lesser lights of lob bowling during the turn of the century, who, nevertheless, were some of the greatest names in cricket in their days.

The stylist who was also a lobster

A striking name in this curious list is that of Lionel Palairet — one of the most elegant batsmen of all time, a stylist to his core. David Foot, the greatest expert on Somerset cricket, called him ‘probably the most stylish batsman to play for the county.’

In his fact-rich, informative biography of Palairet, written for the Association of Cricket Statisticians, Darren Senior summarises, “He had a fine career as a graceful batsman, but also as a useful lob bowler, good outfielder and stand-in wicketkeeper who, although lost too early to business, left a fine record for Somerset.”

Perhaps Palairet did not bowl enough to merit detailed discussion of his methods as a lobster. In fact, in spite of Senior’s assessment, he hardly bowled other than occasionally in the latter part of his career. Acknowledged as one of the best batsmen of the country, he had no reason to fall back on a curious trade.

Yet, when he began his career, Palairet had shown immense promise as a valuable all-rounder.

It was in 1892, his first full season for Somerset and his summer as the captain of Oxford, that saw him at his peak as a lob bowler.

The first match of the season for the University men was against the Gentlemen of England, and the latter won easily by 10 wickets. However, Palairet came on as first-change after some erratic overs of fast bowling by a strapping young Oxford student by the name of CB Fry. He proceeded to capture 5 for 98 in the Gentlemen’s first innings, following it with a polished 49 when Oxford batted for the first time.

The following match was a thriller against a strong Lancashire side.

Palairet, opening the innings for the University, was bowled by the fearsome Arthur Mold for a duck. Thanks to a knock of 50 by Fry, the Oxford innings amounted to 132.

After this there followed one of the curious sights in cricket. The established Lancashire batting outfit struggled against two under-arm bowlers operating in tandem. Palairet bowled 14.4 five-ball overs to capture 4 for 27. At the other end, a young man called John Barry Wood destroyed the rest of the batting with slow lobs, finishing with 5 for 33. The Lancashire side was bowled out for 88.

Johnny Briggs, the great slow left-arm spinner, responded by raising his game in the second innings. He had already claimed 5 for 34 in the first, and now he ran through the Oxford innings with 7 for 32. Palairet was the only one who mastered him, getting 57 excellent runs out of a total of 105. He fell to an outstanding catch by Frank Sugg in the long field.

That set the target as a nice round figure of 150. It was the left-arm medium pace of George Berkeley which combined with Palairet now. The two men took four wickets each, Palairet claiming the sterling one of Archie MacLaren. Amidst great excitement, Oxford emerged victorious by 7 runs.

Less than a month later, the Oxford men travelled to Old Trafford to take on Lancashire again. This time Briggs and Mold were merciless, capturing 18 of the 20 wickets between them, ensuring a defeat for the University by an innings and 22 runs. But when Lancashire batted, Palairet captured 6 for 84, which remained his career-best figures. When he was not bowling in that match, he kept wickets, a duty he shared with Malcolm Jardine, the father of Douglas.

The next match was at Hove against Sussex. Palairet batted splendidly against a superb attack comprising of Fred Tate, C Aubrey Smith and the famous lob bowler Walter Humphreys. In a low-scoring match he played a couple of brilliant hands, scoring 51 and 75. In the first Sussex innings, he picked up the wicket of Humphreys, as the other under-arm bowler, Wood, captured 4. In the second innings, as Sussex tried to overhaul the target of 235, Palairet opened bowling and finished with 3 for 51, Wood captured 2 for 40. Oxford clinched another thriller by 10 runs.

Later in the season Palairet turned out for Somerset and hit 104 against Gloucestershire and 146 against Yorkshire. He finished the summer of 1,892 with 1343 runs at 31.97 and 30 wickets at 24.13.

Down the years his lobs were not that frequently used by Somerset. And Wood did not play beyond Oxford, ending his career with 53 wickets at 26.39.

However, Palairet did produce some impressive spells from time to time. In 1894, Oxford was at the receiving end with the erstwhile captain turning out for Somerset and capturing 4 for 49.

And of course, for some reason he preserved his bowling feats for Lancashire. In 1895, when Somerset hosted the midland County at Taunton, MacLaren famously hit 424. It was Palairet, used liberally by captain Sammy Woods, who brought an end to the mammoth 363-run association between MacLaren and Arthur Paul by dismissing the latter. He picked three more to end with impressive figures of 4 for 133 even as Lancashire piled up 801.

In his career, Palairet captured 143 wickets with his lobs, at an average of 33.91. However, his best bowling days were at the University, with 52 at 25.03 in the 31 matches for Oxford. Somerset did use him occasionally, but in the 222 matches for the county he managed just 87 wickets at 38.59.

Woods and Sugg

Interestingly, while charting the story of Palairet, we have touched upon a few other characters who did leave a bit of their faint marks on the history of lob bowling.

Frank Sugg, the man who caught Palairet off Briggs with a brilliant effort in the deep during that Oxford-Lancashire thriller in 1892, was a good enough batsman to play twice for England. He was not much of a bowler, his 305-match career getting him just 10 wickets. However, in 1896, against Sussex at Hove, he got the great KS Ranjitsinhji stumped for 165 with one of his lobs.

Two years later, with the players playing out time at Trent Bridge, Sugg tossed up his lobs and dismissed William Gunn and Charles Dench to achieve his career-best figures of 2 for 12.

Woods, the Somerset captain of Palairet, was another occasional lobster.

A fast bowler of considerable pace and ability to intimidate, injuries forced Woods to reduce his run-up in later days and sometimes he resorted to lobs. However, this colourful man recalled that he bowled hundreds of lobs in First-Class matches but never once took a wicket — although plenty of catches and stumpings were missed off his bowling. He even said later that once at The Oval against the Australians, his old friend Gregor MacGregor, a fearless wicketkeeper who stood up to his fastest bowling, was so confused by his lobs that he missed several chances which could have given him a hat-trick. “The bounders proceeded to hit me over the pavilion,” were the words with which he ended his tale.

However, one must make allowances for a faulty memory and a weakness for the good story … because there was no First-Class match where Woods played against the Australians at The Oval in which MacGregor stood as the wicketkeeper. He did bowl a few lobs after straining his side when Australians played Cambridge Past and Present at Portsmouth in 1890; Harry Trott hit 186 and Billy Murdoch 129 in a total of 355 for 6 while Woods had figures of 10-1-41-0. MacGregor was indeed the wicketkeeper in this game, and may be Woods was confused about the venue.

MacGregor himself said that he was never sure whether Woods attached any importance to his lobs or not. Every other occasional lob bowler, from Palairet to Wynyard, had a bit of guile to their bowling. Woods apparently had none when he bowled his lobs.

The Fry fragment

Coming to Fry, we encounter the first striking example of lobs bowled as a last resort.

In 1898, even as the great all-round sportsman was enjoying one of the best seasons with the bat with 1788 runs at 54.18, English cricket was implementing a scourge against throwing. The man entrusted with the job was the Australian born Jim Phillips. A travelling umpire and cricket scout, Phillips had accompanied Stoddart’s team to Australia and had created a sensation by calling Ernie Jones.

In June 1898, shortly after his marriage to the formidable Beatrice Summer, Fry played against Nottinghamshire at Trent Bridge. The umpire was William West, a man who had played for Surrey in 1891 and dismissed Fry with his bowling. He had since umpired four of Fry’s Varsity matches and had found nothing wrong with his action.

However, on this day, Fry was called by West for his action.

It seemed, but a minor hiccup. In the next game, against Cambridge, Fry turned in a brilliant all-round performance, hitting 54 and 62 and capturing 3 for 28. Neither Robert Carpenter nor James Lillywhite, two umpires of great experience, found anything wrong with his action.

Incidentally, Sussex lost the match in spite of Fry’s performance, and the architect of the innings-win for Cambridge was Gerald Winter. A middle-order batsman and lob bowler, Winter scored 80 when Cambridge batted and followed it up with 4 for 34 and 6 for 59 to complete a remarkable all-round triumph. We will touch upon him a little later.

Boosted by this encouraging match, Fry appeared against Oxford next, in his familiar ground at Hove.

He scored 62 in the Sussex total of 301 before being put on to bowl late on the first day. The umpire in his case was Phillips, who, like West, had had no objection to Fry’s action when he had bowled in Varsity matches.

But now Phillips called him. And that, at least to Fry, seemed premeditated. According to him, he was even no-balled when he changed his action and bowled with a rigid elbow. He finished the over with lobs and did not bowl again in the innings.

In his autobiography Life Worth Living Fry’s account is intriguing: “Before the second innings, I had my right elbow encased in splints and bandages and took the field with my sleeves buttoned at the wrist. But old Billy Murdoch, our captain … twisted his black moustache, showed his white teeth, and refused to put me on. I was both astonished and annoyed, but he refused further particulars.”

Well, Life Worth Living is full of such fabrications that fall woefully short of facts. The scorecards indicate Fry bowled four second-innings overs, and an account in verse in Cricket does indicate that the four overs consisted of lobs. Fry seemed to have read about the aboriginal bowler Jack Marsh who, accused of throwing, did have his arm encased in splints. He just ‘threw’ in the story as his own.

In fact, it was the Oxford batsmen who requested Fry to bowl lobs in the second innings, to get some practice with this sort of bowling because Cambridge had Winter amongst their ranks. In fact, the Oxford men also called upon old Humphreys to bowl to them in the nets to prepare against the mystery lob bowler.

Because of his action, Phillips referred to Fry as CB Shy. And later the great hitter Gilbert Jessop made fun of his action with the limerick,

“There was a young batsman named Fry

Who at bowling oft thought he would try

Till an umpire named Jim

Who was looking at him

Said: Good heavens, I call that a shy!”

That was not the last time Fry bowled lobs.

In 1902, Sussex played the Australians at Hove, and Fry’s great mate Ranji was the skipper. Through that season, Ranji had been frustrated with the bowling and fielding of the side.

In this match, the home team had been on top with the Australians struggling at 152 for 5, primarily due to some excellent early work by Albert Relf. But then, Warwick Armstrong hit 172 not out. Monty Noble, dropped several times, went on to score a mammoth 284 not out. The sixth wicket collaborated in a 428-run stand. And Ranji, at the end of his tether, put Fry on as his eighth bowler and came on himself with his leg-breaks as the ninth. Fry bowled 9 overs of lobs that cost him 42 runs.

A few more notables

Coming back to our University bowler Winter, unfortunately, his deeds with the lobs remained limited. The success against Sussex, 80 runs and 10 wickets in the 1898 match at Hove, was his only major accomplishment. For all the apprehensions of the Oxford men, he remained wicketless in his Varsity match, while failing with the bat as well.

He did go to North America with Plum Warner’s team at the end of the 1898 season, but when the following summer took off he had become more of a batsman. He was not overly successful in this role either.

The only other notable deed in his career was the 3 for 62 he managed against the 1899 Australians when included in WG Grace’s XI at Crystal Palace. His haul of Noble, Joe Darling and Jim Kelly do read impressive.

Within a couple of years, though, Winter had disappeared from the scene, his 22 matches bringing him 22 wickets at 23.95.

During the turn of the century, lobs were still being used occasionally, although mostly by irregular bowlers. Some of the exponents were Albert Thornton of Sussex and Kent; Harry Wrathall of Gloucestershire and Francis Quinton, one of the many army-men who played for Hampshire.

Many top-drawer batsmen did not like lobs bowled at them. Tom Hayward, for example, was once dismissed off a high, flighted delivery from the Essex batsman Arthur Turner, one of the worst bowlers in the land.

One more notable name to have bowled lobs was William Gunn. A fantastic batsman who played 11 Tests for England and made over 18,000 runs for Nottinghamshire, Gunn did bowl lobs towards the latter part of his career. One of these lobs dismissed WG Grace as Gunn picked up 3 for 53 against Gloucestershire in 1893. The great man had hit the inviting delivery with great power and Robert Mee at short-leg had somehow held on to the ball.

Gunn turned in useful performances with the ball time and again, such as 4 for 27 against Leicestershire in 1894 and 3 for 37 against the Australians for MCC in 1896. He captured 76 wickets in all, and quite a few were earned with lobs, especially in the second half of his career. However, the only ten-wicket haul of his career came in 1885 against Hampshire, and on that occasion he bowled round-arm slow.

Stoddy’s Mission

There were lobs that were used in Test matches as well.

In January 1898, England faced Australia in the fourth Test of the series at Melbourne. Drewy Stoddart, the English captain, was in the midst of a horrid tour, going through a mix of personal misfortune, material losses and a spate of defeats. When the Test started, Australia led the series 2-1, and they also won the fortuitous advantage of the coin flip.

However, with Tom Richardson and JT Hearne bowling brilliantly, the home team were soon reduced to 58 for 6. But, at that moment the outstanding Clem Hill was joined by the gutsy Hugh Trumble.

165 runs were added for the seventh wicket in a magnificent partnership, Hill producing a breathtaking innings of counter attack. Trumble remained steady at the other end.

When Hill stood at 65 and Trumble 34, the latter was dropped by wicketkeeper William Storer.

Stoddart, at a loss for ideas, brought himself on and proceeded to bowl lobs. The first over cost him 9 runs, and there was a wide in the mix as well. At the other end, he asked Storer to take off his pads and gloves and have a bowl. Frank Druce took up the role of the makeshift wicketkeeper.

The final figures of Stoddart do not look too bad. 6-1-22-0 in a total that was hoisted to 323 by that brilliant 188 by Hill seem quite impressive. In fact, the move of bringing on Storer also came off, because it was the wicketkeeper who had Trumble caught at square-leg for 46. And ‘Felix’, or Tom Horan if we use the real name, did suggest in his report that Stoddart could have bowled some more.

However, Stoddart neither bowled any more in the innings, nor did he play any further for England after the match.

A final few names

Apart from Simpson-Hayward, there were some others who tried their hands at lobs in the first decade of the new century and up to the Great War, although none of them did so with anything approaching success.

One such was Sir Arthur Hazlerigg of Leicestershire, High Sheriff and Lord Lieutenant of the county, who later became Baron Hazlerigg.

Reggie Spooner, who played 10 Tests for England and scored 119 against South Africa at Lord’s in the second Test of the Triangular Tournament, bowled lobs for Lancashire and took 5 wickets for them at 110.80 apiece.

Major Henry Bethune, yet another army-man to turn out for Hampshire, used to blow slow over-arm in his younger days. But in 1901, he turned out at Lansdowne Club, Bath, playing for the Gentlemen of MCC against the Gentlemen of Holland at the age of 56, and finished with 6 for 11 and 10 for 18 with mysterious lobs. The Dutchmen were a strong side, and included men like Carst Posthuma among their numbers, but were totally confused by those tossed up deliveries.

There was also CB Grace, a son of WG, who played for London County in 1900 and picked up 3 for 62 against Warwickshire, his only wickets in 4 First-Class matches. Given that he averaged 8.40 with bat, one can conclude that not much of his father’s cricketing genes had passed through to him.

Later, in 1908, Philip Fryer made his debut for Northamptonshire by claiming 3 for 36 against Leicestershire with his lobs. His primary job was to open batting, and he did a decent job, getting 23. He played another game, against Hampshire, and was bowled by the South African recruit Charles Llewellyn for 11. He did not pick up any more wickets and did not play again.

Henry Stevenson was a much better lob bowler than these gentlemen, but most of his cricket was played in Scotland. When he did play a handful of First-Class matches for MCC and assorted teams during the first few seasons of the century, his 4 wickets came at an expensive 67.25 each. He revelled on fast wickets and sent them across at a brisk pace as well.

There remain two other names who did not get any success with their lobs but have to be mentioned because of their august statures.

MacLaren did send down two overs of assorted lobs against Worcestershire in 1910, being hit for 25 runs in the process. The only First-Class wicket he took, against Middlesex in 1901, was, however, with a brisk over-arm action.

This brings us to the final entry in this motley list.

In 1912, Hampshire played Oxford. Harry Altham, who would become a pioneering cricket historian, was playing for the University men.

A week earlier, Altham had been the final First-Class victim of the lobs of Captain Teddy Wynyard when Oxford had played MCC. Now, with Fry and Edward Barrett in the midst of a massive partnership, he was used as a lob bowler. He had bowled lobs for Repton.

TRENDING NOW

And Fry was missed off his bowling at 150. After this Fry batted with the bat held like a croquet mallet. He went on to score 203 not out and Altham finished with figures of 4-0-20-0.