This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

William Moule: One-Test wonder who became a judge

William Moule's only Test was also the first one played on English soil.

Written by Pradip Dhole

Published: Aug 06, 2018, 11:20 AM (IST)

Edited: Aug 06, 2018, 11:22 AM (IST)

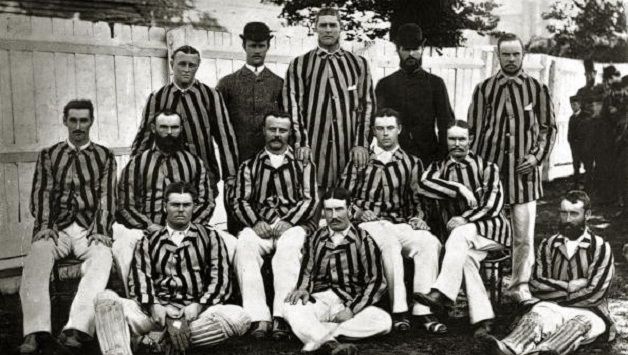

Back, from left: Joey Palmer, William Moule, George Bonnor, George Alexander, Tom Groube

Middle, from left: Fred Spofforth, Harry Boyle, Billy Murdoch (c), Percy McDonnell, Alec Bannerman

Front, from left: Affie Jarvis, James Slight, Jack Blackham

During the period 1880 to 1889, during the infancy of Test cricket, a total of 27 Tests were played between England and Australia, with South Africa joining England and Australia as a Test playing country in 1889, and playing 2 more home Tests against England. During this period of the history of Test cricket, there were 13 Australians who played only one Test apiece in their entire careers: Tom Groube, William Moule, James Slight, George Coulthard, Alfred Marr, Samuel Morris, Henry Musgrove, Roland Pope, William Robertson, Francis Walters, Reginald Allen, John Cottam, and John McIlwraith.

Unlike the modern era, Australian cricketers of the early years were not true ‘professionals’ in the sense that their livelihood did not depend entirely on their participation in cricket. Each man followed a chosen profession as a means of living and played cricket by choice. While they represented a wide variety of professional callings, they were united in their love for, and proficiency at, cricket. Of the two gentlemen sporting bowler hats in the picture above, the one on the left, between Joey Palmer and George Bonnor, had completed his legal studies and had been called to the Bar in 1879. We take this opportunity to bring William Henry Moule, a name from the distant past to present consideration.

A good starting point of the narrative would be with the 26-year-old Mr Frederick George Moule, born in Wiltshire, completing his legal studies and becoming a solicitor in 1847. He then practised his profession in London for a short period before venturing out to the Antipodes on the ship City of Poonah in 1852 as a 31-year-old, accompanied by wife, Julia, née Man. Having arrived at Australia, he decided to work the gold fields in the company of several other young immigrants, despite the fact that the local Government had offered the young men secure jobs.

Disillusioned within a short time, Moule thought it better to move to Melbourne and to set up a private practice pertaining to his legal profession, later joining one Thomas Clarke to begin a law firm. In due course, Moule came to be regarded as an authority on Banking Law, and was for many years the solicitor for the Bank of Victoria, the English, Scottish, and Australian Chartered Bank and the Colonial Bank. He acted in that capacity for all those banks until his demise in 1891.

While in Australia, Moule played cricket and was a member of the Melbourne Cricket Club, filling in the role of Vice-President for a length of time. The multi-faceted solicitor was also a long-standing singing member of the local Church of England choir.

Upon his death, Moule had left behind his widow, three sons, solicitor FA Moule, barrister WH Moule, and sheep and cattle farmer, CG Moule. There were also two bereaved daughters. William Henry, the second son, was born 31 January 31, 1858 at Brighton, Victoria, and was informally known as Billy. He was educated at Melbourne Boys’ Grammar School from 1866 to 1875. There is no documented evidence of his playing cricket for his school.

Moule attended Melbourne University and graduated with an LLB degree in 1879, being admitted to the Bar in the same year. In 1880, he began practising his legal skills with the firm of Vaughan, Moule, and Seddon, his father being one of the partners of the firm. By this time, the 22-year-old barrister presented a well-built and athletic figure, six feet in height.

Moule’s first documented cricket match appears to be a Second-Class fixture for XV of Victoria against the Australian team that had toured England in 1878 under Dave Gregory. The Australian XI won the game by 6 wickets, and Moule scored 3 and 12.

The city of Melbourne saw a new establishment being founded in 1875, essentially a young men’s club going by the name Bohemians Club, with the enigmatic motto: Peradventure. The rules of entry to the club reflected those in force for I Zingari, as follows: “The Entrance fee be nothing and the Annual Subscription do not exceed the Entrance.”

Young men from the same families that supported the Melbourne Club flocked to be part of the new venture. The club played cricket in the summer months and staged theatrical performances in the winter months.

One of the young men who had been attracted to the new club’s colours was Moule, in 1878-79. He played 4 games for the club over two seasons, including one against the visiting Lord Harris’ XI at Melbourne, turning out for XV of the Bohemians and scoring 3 and 7.

He made his First-Class debut later in the month, playing for Victoria against Lord Harris’ XI at MCG. The visitors put up 325, William Cooper taking 5 for 79. Introduced as eighth bowler, Moule captured 1 for 24. In response, Victoria recovered from 9 for 3 to 261, thanks to Don Campbell (51) and Jack Blackham (46). Last man Moule got 17 not out. Tom Emmett had 5 for 93 from his 63 overs. The visitors were then dismissed for 171, George Ulyett scoring 48. Victoria won by 2 wickets, Moule scoring 6 from No. 3.

There was another match a fortnight later against the same opponents at MCG. This time the visitors totalled 248, Palmer picking up 6 for 64 from his 34 overs. The home team scored only 146. Emmett (6 for 41) was the pick of the bowlers again. Johnny Mullagh, the legendary indigenous cricketer, scored 4. Asked to follow on, Victoria folded up for 155, Mullagh top-scoring with 36 and Emmett taking 5 for 68. Lord Harris’ XI won by 6 wickets. Moule’s contributions in the game were 13 and 2.

Followers of cricket history will remember the acrimony surrounding the early termination of the 1878-79 England tour of Australia following the infamous Sydney Riot, during which Harris had reportedly been assaulted by some spectators during an episode of “civil disorder” following the run out decision given against local favourite Billy Murdoch by Victorian umpire George Coulthard, who had been attached to the English camp. An aggrieved Harris was quick to lead his team away from Sydney and steadfastly refused to play the return match against a representative Australia XI that would have been the fourth Test in history.

Harris being a stalwart of the cricket establishment of England, it was only to be expected that the unfortunate incident at Sydney was going to have severe repercussions in the following English season (1880), during which an Australian team under Murdoch was to tour England. To add to the confusion, a team calling itself The Gentlemen of Canada was also scheduled to tour England in the same summer.

James Lillywhite Jr, in his capacity of English agent of Melbourne CC, who were in the process of organising the 1880 tour, encountered many obstacles in his path. As if the riot incident had not been enough to put the England powers that be off from welcoming the Australians in 1880, it was the perceived ‘mercenary’ attitude of the so-called amateurs from Australia that proved to be an even greater deterrent to the tour. It was relatively late during the Australian summer of 1879-80 that Lillywhite was able to persuade the English authorities accept the tour programme.

By then, however, the English domestic schedule had already been finalised. It became difficult to get matches against the major counties or at the major venues. As has already been related in these columns earlier, Lillywhite had to take recourse to placing advertisement for fixtures in The Sporting Life.

Even then, most of the offers were for ‘odds’ games pitting XVs or XVIIIs from local teams against XIs from among the Australians. During the course of the tour, however, the unexpectedly high standard of play exhibited by the Australians in the preliminary games forced the English cricket think-tank to reconsider their rigidly negative attitude towards the visitors from the Antipodes.

Sympathising with the plight of the Australians, WG Grace tried to arrange a game for them at Lord’s, but MCC had turned the idea down out of hand, citing non-availability of the venue. It was finally left to the Surrey Secretary Charles Alcock, with Grace as an able mediator, to persuade the establishment to allocate a match against the Australians at The Oval, albeit right at the end of the season.

Alcock’s silver-tongued oratory even moved Harris, still smarting from the memories of Sydney, to exert himself in selecting a suitably representative England team to confront the Australians in what would turn out to be the very first Test played in England.

It may be worth remembering at this point that the Australian tour party that had embarked under Murdoch on the SS Garonne from Melbourne on March 19, 1880 for the eight-week voyage to the Home Country, had consisted of only 12 players. One of them, ‘Affie’ Jarvis, was included as an understudy to the incomparable Blackham as a second wicketkeeper. George Alexander had accompanied the team as manager, sharing duties on the tour with Harry Boyle.

Writing in For Club And Country, Ken Williams, a volunteer for the Melbourne CC Library, states that Moule was reportedly selected for the tour very late, just about a week before the party embarked on their journey, and then only because several other players, notably, Frank Allan, George Bailey, Tom Garrett, Gregory, and Horan, were not available for the tour.

Elaborating on the cricketing abilities of Moule, Williams says: “He was an attractive batsman, whose strength lay in his off side strokes, and a useful medium pace bowler. An athletic fieldsman, he possessed a particularly fine arm.” Moule had been selected for the tour squad on the very scanty evidence of his form in his only two First-Class games till then, both against Lord Harris’ XI in early 1879.

Writing in It’s Not cricket, Simon Rae has very definite views about the first ever Test played in England: “It is a little known — or little reflected on — near-certainty that England won their first-ever home Test match, at The Oval in September 1880, as a result of throwing.”

Quickly absolving the group of bowlers who had actually played in that Test, Fred Morley, AG Steel, Alfred Shaw, Grace, Billy Barnes, EV Lucas, and Frank Penn, of any wrongdoing, he plunges into the strange drama that had been played out at Scarborough.

For the Australians, there was to be a defining moment of the tour in this Second-Class game against XVIII of Scarborough. The home team had ten men with First-Class experience, and this was the first game of the tour in which the touring Australians were defeated, going down by 90 runs. This game was to upset the balance of the team and to provide an unexpected window of opportunity for one of the tourists.

The villain of the piece was an amateur right arm fast bowler named Joseph Frank who was to play only a handful of First-Class matches, and only one for his native Yorkshire. Acknowledged as being “very fast”, the brevity of his cricket career was explained very bluntly by a comment appearing in the Who’s Who of Cricketers, as follows: “His bowling action was very suspect.”

At Scarborough, the local team scored 170, Fred Spofforth (9 for 72) and Palmer (4 for 44) doing most damage. At the end of the first day, the touring Australians were in dire straits, the scoreboard reading 33 for 7, a mini recovery in reality, considering that the fourth wicket had fallen at 3. Frank was introduced into the attack rather late and captured the last two wickets to fall. His action was noted as being patently unfair.

At the end of the innings, Murdoch spoke to the skipper of the XVIII, Henry Charlwood, about the dissatisfaction of the Australians about Frank’s action. Nothing had come of that. In fact, it had been reported at the time that Murdoch was brusquely advised to “mind his own business.” In desperation, Murdoch spoke to Frank himself about the misgivings surrounding his bowling action. Nothing came of that either.

One of the tourists, reporting to the Sydney Mail, had this to say about the events that unfolded during the second innings when Frank was introduced early: “[Alec] Bannerman, after getting a severe blow on the leg, objected, and drew away from the wicket. Murdoch then went out and asked Charlwood to discontinue the unfair proceedings, as it was not fair cricket, besides being very unfair.”

When there was no response from the home skipper, an appeal was made to the umpire, who is reported to have replied: “Some of the balls were unfair, but it was very difficult to catch them.”

When the game proceeded without any intervention from the umpire, Frank was allowed to bowl again. Perhaps emboldened by the indecision of the umpires, Frank then began to “throw in such a way that not only did he get the batsmen out, but hit them so frequently, and with such force, that it caused them to limp about the ground in the most painful manner.” The spectators, however, derived much amusement from each palpable hit on the batsmen.

It was during this period of play that Frank hit Spofforth a crunching blow on his right (bowling) hand that broke the bottom joint of his third finger. The injury caused Spofforth to miss the rest of the tour, including the solitary Test. Up to this point of the tour, Spofforth had captured 393 wickets in all classes of cricket, and his unavailability for the rest of the tour was to be a crushing blow for the Australians, and was to tilt the balance in favour of England for the Oval Test.

England included as many as eight debutants in the Oval Test. The presence of the three Grace brothers, EM, WG, and GF, provided the first instance of three brothers playing for a team in the same Test. The Australian team boasted seven debutants, with Alexander, manager of the team, called in as a replacement for the injured Spofforth.

Quoting Wisden, Gideon Haigh says in Endless Summer: “In the history of the game no contest had created such world-wide interest; that the attendances on the first and second days were the largest ever seen at a cricket match; that 20,814 persons passed through the turnstiles on the Monday, 19,863 on the Tuesday, and 3,751 on the Wednesday.”

Martin Williamson writes that Harris, thankfully having apparently recovered his equanimity after the travails of the Sydney Riot, won the toss for England “in glorious late-summer sun”, and sent the two elder Grace brothers, EM and WG, to launch the innings at about 11 in the morning.

As always, Charles Davis has the fine details of the Test beautifully worked put. England ended the first day on 410 for 8 in 199 four-ball overs. The elder Graces gave the innings a substantial foundation with a stand of 91 in 81 minutes, before EM (36) was dismissed.

WG, batting on 48, then welcomed Lucas to the wicket, and the two of them put up a commanding stand of 120 before Lucas (55) was dismissed. In the meantime, WG had inscribed his name in the annals of cricket history by becoming the first English batsman to score a century on Test debut, his century coming in the 100th over, in 212 minutes.

WG was fourth out, of 281, having scored a wonderful 152 in 251 minutes, and containing 12 fours. Harris did his bit, scoring a reassuring 52, while Steel contributed 42 to the total. Alexander picked up the wickets of Barnes and Harris. Retrospectively awarded Baggy Green # 22, Moule, the sixth man in the bowling sequence, was introduced as late as the 184th over, with the total reading 359 for 5, and disposed of GF Grace for a duck in his seventh over.

In The Complete Illustrated History of Australian Cricket, Jack Pollard reports a drizzling rain overnight that caused the game to begin five minutes late on the second day, play starting at 11.05. The English innings was quickly terminated and Australia were batting at 11.40 in the morning. Moule turned out to be the most successful Australian bowler, with 3 for 23. The innings lasted just short of six-and-a-half hours.

The first Australian wicket fell after 22 minutes of play by which time 28 were scored. Murdoch was the first to go, out for a duck after facing 19 deliveries. It was left to Bannerman (32) and Boyle (36*) to put together something of a total. Moule contributed 6. The Australian innings was over in just over two-and-a-half hours for an inadequate total of 149. Morley (5 for 56) and Allan Steel (3 for 58) ran through the Australian innings.

Harris invited Australia to follow on, and Bannerman was back opening the batting, this time accompanied by Boyle. The third wicket went down with only 14 on the board, before Murdoch and Percy McDonnell (43) put up a stand of 83 valuable runs. The skipper was batting on 41 at this point. Slight followed almost immediately. Blackham (19) and Murdoch then collaborated for 42 runs.

Much was expected from Bonnor, but he could score only 16. The eighth wicket fell at 187, with Australia still 84 in arrears. Alexander stepped into the breach at and added 52 with his skipper, before being caught in the slips by Shaw off Morley for 33. The total at this juncture was 239 for 9, and Australia were still trailing by 32. An innings victory seemed to be on the cards for England.

In the meantime, Murdoch brought up his maiden Test century in the 124th over, off 251 deliveries. The match, then, was to witness two maiden centuries, one from each camp. The stage was now set for a combination of legally trained brains to take up the challenge. As it turned out, both Murdoch and last man Moule had completed their respective legal studies in 1879, the former becoming a practising solicitor, with the latter being called to the Bar in the same year.

The combination produced 88 for the last wicket in 90 minutes of cautious cricket, the highest partnership of the innings. When Moule (34 off 99 balls, 4 fours) was out, England needed 57 runs to win. Murdoch remained undefeated on 153 (in 316 minutes, facing 358 balls, and hitting 17 fours). This 1-run advantage on WG’s 152 was to result in a gold sovereign being presented to the Australian skipper as a result of a wager between two old friends.

Harris had perhaps considered the victory a mere formality. In any case, it was the combination of ’keeper Lyttelton and GF Grace that came out to knock off the required runs. Fate was to play unfair with GF, however. He was dismissed off his second ball for a “pair”, the first in the history of Test cricket.

The unfortunate Fred Grace was to catch a chill and pass away quite abruptly from its consequences on September 22, 1880, barely a fortnight after the conclusion of this Test. Even so, all other considerations being set apart, the Oval Test of 1880 still remains famous for one high point in the short life of Fred Grace, despite his “pair” on debut.

In the Australian first innings, Bonnor was caught by Fred Grace off the bowling of Alfred Shaw for 2. This is how it came about, from the description given by SF Charlton, who had been witness to the feat. Haigh, referring to the reminiscences of the gentlemen named in Endless Summer, says: “Shaw, bowling from the Vauxhall end, had made a hand gesture to Fred Grace alerting him to the fact that something was about to come his way. Bonnor had then misjudged the flight of the ball and had had a mighty heave at it. It had steepled up towards Fred waiting for it near the sightscreen. The ball had gone so high in the air that Bonnor and Boyle had run two and were in the process of going for the third when Fred Grace had made the difficult catch that is still spoken of with respect. Legend has it that the measured distance from the position of the batsman to the spot where Fred Grace had taken the catch had been measured at 115 yards.”

Coming back to the Oval Test, the fifth England wicket fell at 31, with 3 of them going to Palmer, before EM was joined by WG. The two experienced players then went about their business of scoring the 26 needed, and England ended up victors by 5 wickets.

It is interesting to note that the Australians of 1880 played only 9 First-Class matches on the tour, one of them being the Test. It is also worth taking cognisance of the fact that Moule was not in the team for any of the 4 First-Class games preceding the Test, Alexander being included in the playing XI in all of them. On the other hand, Moule was included in the team for the ill-fated game at Scarborough that resulted in the hand injury to Spofforth, while Alexander is seen to be sitting out this particular game. Moule played in the 4 First-Class matches following the Test, but with moderate success.

Back home in Australia, his First-Class career was to include only two more First-Class games, both at the MCG for Victoria against New South Wales, one from Christmas Eve of 1881 and the other from Boxing Day of 1885. Although his performances in both the matches were very mediocre, Victoria won both matches, by 2 wickets and an innings and 69 runs.

Moule’s First-Class career was done and dusted after these two matches. He was not even seen in Second-Class games after 1881. Meanwhile, his professional career was on the ascendency, his most celebrated court case being known as the Buckley Will Case of 1882. The local media began referring to him as “the fiery young advocate with strong political ambitions.”

He represented Brighton in the Legislative Assembly from 1884 to 1900 after defeating the highly fancied Sir Thomas Bent by a margin of 1579 votes to 925, the event being celebrated at the time in the media in the following ditty:

“When Moule appeared in Brighton first,

The story to him went,

That he would but his boiler burst

In steaming against Bent.

The undertaker, they declared,

Could only Tommy fight;

But Moule took up the ball, prepared

To bowl instead of SLEIGHT

The figures up, a mighty laugh

The gladdened heavens rent,

And then they wrote Moule’s epitaph —

“THE MAN WHO PUT OUT BENT”

Moule later chaired royal commissions on law reform (1897) and factories and shops law (1900), and adorned the Bench as a County Court Judge from 1907 to 1935, specialising in insolvency cases. Commenting on his demeanour as a Judge, The Age had commented at the time: “He had a genial disposition, and though the hardened criminal had reason to fear his caustic comments with the sentence to follow, first offenders were treated with leniency and kindly advice”. He became a reporter for the Victorian Law Reports, and in 1905 succeeded the late Judge Box as editor of that journal.

In 1885, Billy Moule married Jessie, daughter of Henry Osborne, and raised a family of two sons and a daughter. One of his sons, Humphrey, was killed at Gallipoli in August 1915. His other son, also with the initials WH, followed the legal profession, becoming a solicitor in his father’s firm. Judge Moule retired from the County Court Bench in 1935 on account of ill-health, and passed away on August 24, 1939 at St Kilda, Melbourne. At the time of his death, Moule was the last-surviving member of the 1880 Australian Test team that had played the 1880 Test.

TRENDING NOW

Obituaries Australia states: “The funeral [procession] left St Andrew’s Church, Brighton, after a service conducted by Archdeacon H. B. Hewett. At the Brighton Cemetery a service was conducted by the Rev. F. Godfrey Hughes. The chief mourners were Judge Moule’s son, Mr. W. H. Moule, and his nephews, Messrs. Adrian and Morris Court. Also present were Canon E. S. Hughes and Major-General F. G. Hughes and a few close friends.”