This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Ashes 1907-08: Victor Trumper masterclass to finish off a classic Ashes series

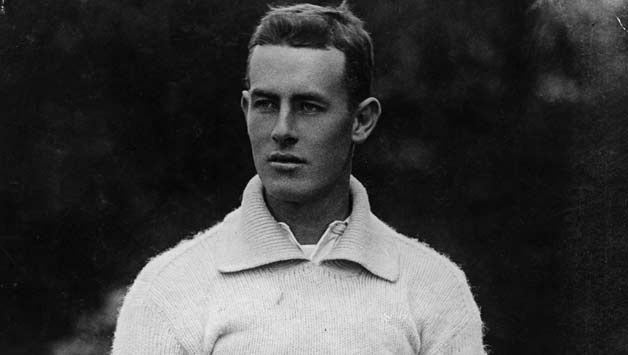

The fifth and final Test match of the dramatic and criminally forgotten 1907-08 Ashes series saw another see-saw battle in which Victor Trumper made all the difference.

Written by Arunabha Sengupta

Published: Apr 21, 2016, 09:57 AM (IST)

Edited: Apr 27, 2016, 01:07 PM (IST)

February 27, 1908. The spectacular sequence of Tests had been cruelly affected by rain at Melbourne, helping Australia to clinch the Ashes after the fourth encounter. However, that did not prevent the fifth and final Test from becoming another classic. Arunabha Sengupta looks back at the final Test of that epic but forgotten series that saw Victor Trumper roar back into form to carry Australia to a win from behind.

Battle scars

After three titanic battles at Sydney, Melbourne, and Adelaide the weather had dampened the English cause when the series had returned to Melbourne for the fourth Test. Caught on a sticky wicket, the England side had surrendered the Test and thereby the Ashes.

By then the visitors were tottering from the epic exchange of blows.

Wicketkeeper Joe Humphries had suffered from heat stroke during the second Australian innings at Melbourne. He had undergone an operation and was still recovering in a Melbourne hospital.

The maverick and brilliant all-rounder Jack Crawford had been examined by the Melbourne physician Dr Strong and the diagnosis had been a strained right side of the heart. Additionally, he had lost a stone since the beginning of the tour. He was advised rest and further told to consult a London doctor before resuming cricket.

The opening bowlers were both carrying injuries. The great Syd Barnes had strained a leg, and missed the tour match against New South Wales. Arthur Fielder, the most successful English bowler of the tour, was having problems with the knee.

Captain AO Jones had returned from sick bed to play in the Melbourne Test and continued to lead the side, but he was far from being at his fittest.

It did not help matters when the interim match against New South Wales also turned into a marathon cliff-hanger contested over six days.

The home side scored 368 in the first innings, thereby taking a 70-run lead. Fielder was used sparingly by Jones, the captain’s eye focused on the Test match. But even then he sent down 31 overs and his knee was busted by the time the innings ended. Additionally, he had damaged his elbow, and it refused to yield to treatment. Fielder did not bat or bowl in the second innings of the sides, and was in no shape to take the field in the final Test. READ: Rhodes, Hill, Trumper, Haigh: How believable are player memories?

The state team, without Test stars Monty Noble, Syd Gregory, Hanson Carter and Tibby Cotter, made a brave attempt to get the required 387 for victory. They were 375 for 9 at the end of the sixth day when the match was called off as a draw because the Test was scheduled to begin the following morning.

With the English bowling resources depleted to wafer thin levels, and the series already lost, speculations were rife about a non-contest. But, this series had been scripted by the cricketing gods.

The men rallied around. Barnes decided to play in spite of the injury. Crawford pulled on his boots in spite of the strained heart and loss of weight.

And by the end of the first day’s play, they had Australia on the ropes. It was an incredible display by the valiant tourists.

England on top

Captain Jones won the toss and boldly sent the opposition in. It was a clever decision, albeit a courageous one. Recent rains had rendered the wicket soft, and although not really expected to be unplayable it looked good for the bowlers. The Bulli soil ensured that the Australian wickets dried fast, but when the coin was flipped there was no sun and the wind was strong.

Trumper, who had scored three ducks in the last three Test innings, was held back down the order. Young Charlie Macartney opened the innings with captain Noble, and was quickly caught in the slips off Barnes.

But thereafter, for a while, it looked that the brave ploy of Jones would backfire. Jack O’Connor, promoted from his usual position in the tail to bide time while the wicket was at its worst, played slowly but with assurance. At the other end Noble batted with easy elegance. Wilfred Rhodes, whose left-arm spin was expected to be ideal for the wet wicket, found the track unresponsive. And Barnes, with the wind behind him, was bowling below his best. READ: Victor Trumper unveils new facet of his genius during his 208 against Queensland

Jones saw as much from the slips, took off Barnes and introduced Crawford. After a few overs, he sent Rhodes to patrol the covers and brought on Barnes from the other end, to bowl into the wind. And immediately things started to happen.

Crawford was bowling his medium pace, mixing it up with occasional off-breaks. O’Connor edged him to the keeper. Barnes curled one past the broad blade of Noble and hit the stumps. Clem Hill latched on to a short ball from Barnes and pulled hard, but Keith Hutchings dived sideways at short-leg and brought off a spectacular one-handed catch. Warwick Armstrong pushed one back to Crawford. Trumper was held in the slips off Barnes.

The Australians were using Macartney and Armstrong as specialist bowlers, and had sent O’Connor to negotiate the wet wicket. As a result they batted really deep. Vernon Ransford came in at No 8, Roger Hartigan at No 9. Both were specialist batsmen and in excellent form. The combative wicketkeeper Carter was the No 10. But on this day, Barnes and Crawford ran through the side. Only Gregory, with his vast experience, managed to negotiate some anxious early moments against Crawford and play a steady, sedate innings.

The wicket was not particularly difficult. Only the very short pitched deliveries rose awkwardly. There was turn available for both the bowlers, but it came slowly off the pitch. Yet, Australia folded for just 137 within two and a half hours. Barnes picked up 7 for 60. Crawford 3 for 52. The two of them and Rhodes, that was all the bowling that England required.

The English innings started disastrously as well. Noble opened the bowling and his first ball was pushed for a single by Jack Hobbs. The second delivery was virtually unplayable and bowled Frederick Fane.

But thereafter the spectators witnessed some wonderful batting.

The Sydney Cricket Ground went on to become the favourite venue of Hobbs. Down the years, he came to love the picturesque stands, the green playing area, the huge scoreboard and the colourful characters on the famous hill. The affection this great batsman developed for the ground was lasting. In 1963, in the very last newspaper article he ever wrote, Hobbs observed: “Sydney had everything. Fielding was a delight because, no matter what your position, you could depend on the ball coming true … The light was perfect from the angle of the batsman. Sydney was the pitch of pitches as I knew it — on which the fellow with the bat could do things to that ball, because the ball did what it should.”

On this day, he played solid cricket, careful yet ready to take advantage of anything loose. Several times he unleashed his famous pull shot to short deliveries. George Gunn, playing in his first and by far the best ever series, struck the ball well. The Australian bowling, without the injured Cotter, was not really deadly.

Even when the wind had dried the wicket and made it faster, the batsmen refused to be troubled. When the light deteriorated and play came to an end with the clock showing five minutes to six, England were at a commanding 116 for 1, Hobbs on 65, Gunn 50. READ: Victor Trumper takes over the baton of batsmanship from WG Grace

Holding on to the advantage

There was heavy rain on Friday night, but a strong drying wind, almost half a gale, ensured that play could start on time. Somehow, with the downpour, the overnight confidence of Hobbs seemed to have deserted him. He added 7 rather unclean runs to his score before losing his stumps to Jack Saunders. But by then England were just two short of the Australian total.

The lead was taken and Hutchings executed a few fluent strokes. Gunn was batting with plenty of chutzpa. And now, with the partnership looking ominous, there was a terrible misunderstanding. Gunn drove firmly to mid-off and gave the indication of starting to run. Hutchings took off at full tilt, his eyes towards his destination at the other end. By then, however, Trumper had gathered the ball swiftly with his left hand. He threw to the wrong end, but Hutchings was too far down the track. The ball was lobbed back to the bowler and the disappointed batsman trudged back even before the bails had been taken off.

Gunn was now joined at the wicket by Joe Hardstaff and the two played comfortably till the skies opened up. The players rushed in and no play was possible for the rest of the day. England were on 187 for 3, Gunn on 77. As rain pelted down incessantly on Saturday night, through Sunday and Monday morning, the advantage clearly rested with the visitors.

The situation was made even worse for the Australians because as play started at half-past three on Monday, there was a weak sun, slow wicket and a promise that the track would get really tough with time.

A brave ploy does not work

When Hardstaff was dismissed almost immediately on resumption, Jones opted for the strategy of making quick runs while the wicket was still playable.

Thus Crawford was sent in to push things along. But he returned after a well struck boundary. The next man in was the leg-spinning all-rounder Len Braund. Gunn held his end firm while the Somerset man forced the pace. 48 runs were added between the two of which Braund made 31 in quick time.

Gunn completed his second century of the series, a more sedate effort than the brilliant knock of the first Test, but by no means a less remarkable one. The rains meant that he had to play himself in several times. And curiously, he had to use as many as seven bats during the innings.

With the wicket becoming difficult, and the sunshine promising to dry it out, Jones opted for the brave ploy of deliberately sacrificing the final few wickets. Rhodes, wicketkeeper Young, the captain himself and Barnes all got out intentionally, the idea being to force Australia to bat in poor conditions. Gunn remained unbeaten on a chanceless 122 and the lead was 144. READ: Victor Trumper Junior — a life spent in his father’s shadow

However, the captain’s policy did not meet with success. The heavy roller ensured a comfortable wicket and Noble countered by striding out with O’Connor in company.

There was only one moment of luck when O’Connor was put down at short leg. But for the rest of the afternoon the two batted defensively, eschewing risks, and managed to play out the period to stumps without being separated.

Noble had enough class to negotiate the dangers of the wicket, and O’Connor applied himself brilliantly, taking full advantage of being left-handed. The score at the end of the day read just 18 without loss, but the most important phase of play had been negotiated.

Trumper returns to form

The following morning O’Connor provided some more obstinate resistance before Barnes sent down a delivery too good for a lower order bat. That brought Trumper into the fray.

This most supreme of batsmen had been having a torrid time in the Test matches so far. His previous five innings had brought 4,0,0,0,10. The sequence of ducks of the hero had been perceived as a national disaster. The first innings effort in this Test had done little to dispel the growing doubts that the great career was on the wane.

Even in this innings the start was anything but confident. The first two balls from Barnes rose awkwardly, the second striking him on the gloves. The third darted in and rapped him on the pads. Up went the Englishmen. But William Hannah’s stentorian ‘Not out’ echoed around the ground.

He had scored just a solitary run when he pushed forward tentatively to Barnes. The ball dangled in the air, not very easy, but eminently catchable at silly mid-on. Rhodes got his hands to the ball, but could not hold on.

That was all the luck Trumper needed. And perhaps that was all that Barnes could withstand in terms of blows of fortune. As the dashing knight of Australian cricket began to strike the ball with customary élan, the bowling of Barnes lost its sting.

Rhodes made some sort of amends, but at the other end. With the score on 52, a ball from the Yorkshire all-rounder went straight through and trapped Noble leg before for a vital 34. This brought Gregory to the wicket.

Once again, this stalwart’s start was hesitant, nervous. But the wicket had eased by now, and soon he grew in confidence. At the other end Trumper was stroking the ball with every bit of aesthetic brilliance that characterised him.

Very early in the innings there were indications that a typical Trumper delight was on the cards. So it proved. As England’s manager Major Philip Trevor wrote in his account of the tour, “Judged, perhaps, strictly by the standard of what he has many times before shown himself capable of doing, this particular innings must yield in intrinsic merit to several others which he has played. On the other hand, when it is remembered how confidently it had been taken for granted that the great Australian batsman would never again play in his own distinctive fashion, this exhibition of his powers is entitled to rank very high.”

The hasty trait of writing off great cricketers during their lean patches was as prevalent in 1908 as it is now.

Gregory soon started playing all his old familiar strokes in his old familiar way. Trumper, at the other end, reached his half century in 94 minutes. The two Australian batsmen gradually closed in on the English lead. Given the number of twists and turns of fate the series had already witnessed, it was very apparent that it was still anyone’s game.

With Barnes unimpressive by now and Braund bowling well but without luck, the resources of England now looked thin. Crawford tried as gamely as ever, but by the time his off-break breached the defence of Gregory to bowl him for 56, Australia had taken the lead. Trumper and he had added 114 in 85 minutes.

Macartney came in next, the young man still not fixed to a particular batting slot in the line-up. The tireless Crawford moved one away and got him caught in the slips. The Australians were just 48 ahead, four wickets down. But Trumper was batting in a sublime zone.

And joining him at the wicket was the other great batsman of the side, Hill.

It did seem that Hill came out with the intention of dominating the disheartened bowlers. He essayed quite a few strokes, trying to hit the ball too hard. But, the important thing is that he survived the initial moments and soon the partnership blossomed.

England bowling missed Fielder. Barnes tried hard, but could not rediscover his edge. Trumper drove him magnificently to the off-side pickets to bring up his century in 174 minutes. When Barnes went in during the lunch and tea intervals, he rolled up his trouser leg. The swollen knee had become more swollen and looked rather sinister.

The only close shaves that the batsmen had during the partnership was against Braund. With a bit of luck the leg-spinner could have bowled both of them.

Trumper celebrated his century by indulging himself in a series of tantalising pulls and drives. The runs cascaded along and the final fifty runs from the flashing blade came in just 50 minutes. Finally, he tried to hit Rhodes to the on side. The leading edge flew over the head of the bowler and Gunn ran across from mid-off to take the catch.

The great innings had ended at 166, essayed in four hours, studded with 18 boundaries. The applause that accompanied him as he walked back was described by JC Davis as ‘zestful’ and ‘fully merited.’

Piling it on

The score was 300 for 5 with plenty of solid batting to come. In walked Armstrong, the batting hero of the previous Test.

The tireless Crawford induced a snick off Hill for 44, but the score was looking more imposing by then. 342 for 6.

Additionally, the injuries continued to bog the visiting cricketers down. Hardstaff’s leg now gave away, an old niggle taking on intimidating proportions. He hobbled out and, in these desperate times, the most fragile member of the side, Colin Blythe, trotted out to field for him.

As Blythe stood in the boundary line, a sympathetic member of the crowd said to him, “You people do have extraordinary luck.” Blythe gruffly responded, “I wish we did. We have come to regard this sort of thing as our ordinary luck.” It summed up the situation.

Australia ended the day at 357 for 6, Amrstrong and Ransford at the wicket, firmly back in the game and perhaps a bit ahead as well.

On the wrong side of rains, again

Heavy rains in the night rendered the outfield soggy and delayed start till one o’clock. Hardstaff did not take the field. More importantly for England, neither did Barnes.

The wicket was now a difficult one to bat on after all the rain. With the bowling without Barnes and Fielder, the Australians rightly opted for the forcing approach. Ransford held one end up while the others chanced their arms. Carter was especially impressive, striking four boundaries in a quarter-hour cameo amounting to 22. By the end of the innings, Australia led by 278. The bowling had been shouldered by Rhodes and Crawford.

Rhodes had sent down 37.4 overs to capture 4 for 102. It was some sort of redemption after a torrid series with the ball for the Yorkshireman that ended with 7 wickets at 60 apiece. Crawford bowled 36 overs and returned with 5 for 141. We need to remember that after the Melbourne Test Crawford had been advised not to play any further.

On this wicket, rendered treacherous by rain, England started out at 3:15 to try and get 279 for an unlikely win.

The start was anything but promising. Fane was dropped by Trumper at slip off the first delivery he faced. The lucky break did little to help England’s cause. Hobbs soon succumbed to Saunders. Macartney’s left-arm spin proved effective on the wet wicket. Gunn and Hutchings were bowled by the young man from West Maitland within four runs of each other.

Hardstaff batted with a runner, but the restricted mobility cramped him up. It perhaps brought physical relief when Saunders bowled him for 8. Braund did not trouble the scorers. England were down to 57 for 5.

Even as Rhodes started to bat really well, Noble curled in a wicket delivery to get rid of the persevering Fane to make it 87 for 6. It was at the near-literal eleventh hour that Rhodes got some support from the wicketkeeper Young. Further damage was prevented on the wretched wicket and England retired for the night tottering at 117 for 6.

A last ditch effort

The task of getting 162 to win was always going to be near impossible, but the wicket rolled well the next morning. After the left-arm medium pace of Saunders had quickly accounted for Young, captain Jones came out to lend Rhodes some solid support. It was the last ditch effort of the Englishmen.

There was excellent judgement of the deliveries, and calculated attacking strokes. When the pair remained unseparated for almost an hour, an English victory crept into the realm of serious possibility. But Armstrong, sticking to nagging leg theory, turned one of his leg spinners enough to beat the bat of the England captain. Jones walked back for 34.

Rhodes found another able ally in the determined Crawford. For nearly another half an hour, they fought on. But then there was the superb Australian captain. Noble was ready to play second fiddle to the big guns in his army, but he was as useful as any of them. In the series, his 396 runs totalled second only to Armstrong’s 410, beating both Hill and Trumper on the way. And while he took just 11 wickets, those scalps came at crucial moments and without too many runs in exchange. READ: Victor Trumper, with sublime grace, strikes his highest Test score

Now the vagaries of his swing ended the resistance of Rhodes, bowling the all-rounder for a fighting 69.

Barnes, dragging one of his legs rather painfully, emerged at 198 for 9 with 81 runs remaining to be scored. But neither he nor Crawford were ready to give in without a formidable scrap.

They batted together for half an hour and added 31. Barnes struck two boundaries. Crawford, off the very last over he faced, struck Saunders sweetly to the cover fence.

But finally Saunders produced a delivery which was too good for the England No 11. Barnes had held his nerve and wicket when he and Fielder had added 39 to snatch a win for England in the second Test of the series. This time the task was a bit too difficult.

England were all out for 229, giving Australia victory by 49 runs in the Test, by 4-1 in the series.

History and hagiography

Following this Test, Victor Daley penned a poem in the Bulletin in honour of Trumper, which included the lines:

Ho Statesmen, Patriots, Bards, make way!

Your fame has sunk to zero;

For Victor Trumper is today

Our one Australian hero.

It followed along the same lines, in a gushing fountain of eulogies. Peter Sharpham, in his biography of Trumper, says that this was written for the hero of the hour.

In retrospect, both the poem and the description of Sharpham were a trifle too hagiographic and highlight the skewed retelling of much of the history of cricket.

It had been an incredible series and through much of it the flashing blade of Trumper had remained dull and unproductive. He had managed 4 and 0 at Adelaide when the series had been turned on its head by the incredible partnership of Hill and Hartigan.

That had been the feat that had decided the series, made more remarkable because Hill had practically got off the sick bed to essay 160. As Malcolm Knox writes in Never a Gentleman’s Game, “England’s resolve had been broken by the Hill-Hartigan stand in the Adelaide furnace.”

If there was indeed a hero of the hour, it had to be Armstrong with his 410 runs at 45.55 and 14 wickets at 25.78, and an economy rate of 2.00 that strangled the English batsmen. There was also Saunders who captured 31 wickets in the series, and Noble who batted, bowled and led the side magnificently. For England, Gunn had been splendid with 462 runs at 51.33 with two hundreds and two fifties. Crawford had literally bowled his heart out for his 30 wickets.

In contrast Trumper’s bat did roar back to form, and in a grand way at that, but by then the series had been decided. His 338 runs at 33.80 read ordinary and is heavily loaded towards that one final innings of 166.

But then, that unfortunately is the way much of cricketing fables are formed.

In his History of Cricket Harry Altham is more accurate in his analysis. He notes that the series was closer than the 4-1 result suggests. In three Tests England ‘played up to a point so well as to have much the better of the argument, [but] each time they allowed the game to slip from their fingers in face of the indomitable fight put up by Australia.’

Brief scores:

Australia 137 (Syd Gregory 44; Syd Barnes 7 for 60) and 422 (Victor Trumper 166, Syd Gregory 56, Clem Hill 44; Wilfred Rhodes 4 for 102, Jack Crawford 5 for 141) beat England 281 (Jack Hobbs 72, George Gunn 122) and 229 (Frederick Fane 46, Wilfred Rhodes 69; Jack Saunders 5 for 82) by 49 runs.

TRENDING NOW

(Arunabha Sengupta is a cricket historian and Chief Cricket Writer at CricketCountry. He writes about the history of cricket, with occasional statistical pieces and reflections on the modern game. He is also the author of four novels, the most recent being Sherlock Holmes and the Birth of The Ashes. He tweets here.)