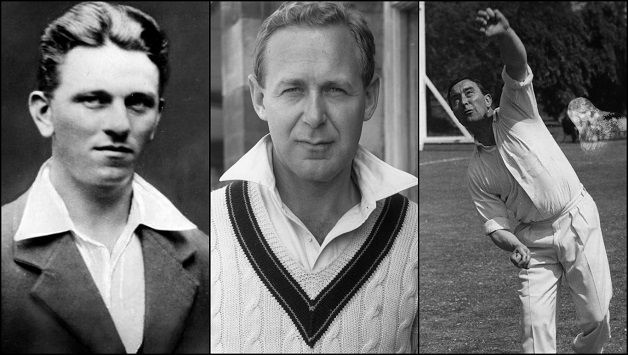

Left-arm wrist spinners in cricket, part 6: Maurice Leyland, Denis Compton, Arthur Morris

From left: Maurice Leyland, Arthur Morris, Denis Compton © Getty Images[/caption] With the English batsmen proving clueless against the left-arm wrist spin of Kuldeep Yadav, Arunabha Sengupta documents the past and present exponents of the art of the Chinaman (oops, left-arm wrist spin) in international cricket. In this episode he covers some batting greats who experimented with this type of delivery, namely Maurice Leyland, Denis Compton and Arthur Morris. Pitifully, top quality Chinaman bowlers were rare in international cricket. There were Ellis Achong and Chuck Fleetwood-Smith in the 1930s and Lindsay Kline in the late 1950s and early 1960s, along with the wrist-spinning aspect of the genius of Garry Sobers. Apart from that very few Chinaman bowlers plied their trade in the Test world. However, three legendary batsmen did turn their hands to left-arm wrist spin, and all of them did bowl in Test cricket with varying degrees of success. Maurice Leyland, the Yorkshire legend and one of the pillars of the England middle order in the 1930s, was perhaps the most accomplished of the trio as far as Chinaman bowling is concerned. In domestic cricket, he formed a formidable combination for Yorkshire alongside pace bowler Bill Bowes and left-arm spinning maestro Headley Verity. He scored over 33,000 runs in First-Class cricket and captured 466 wickets, and still remains one of the select three men to have scored more than 25,000 runs and captured 400-plus wickets for Yorkshire. The other two are, well, George Hirst and Wilfred Rhodes. Having started his career bowling left-arm orthodox, Leyland decided to change to the style that brought the ball into the right hander. It provided Yorkshire — who boasted names like an elderly Wilfred Rhodes, Roy Kilner, and Hedley Verity amongst them — with something different. He would probably not have got a bowl otherwise. Later Wisden wrote in his obituary: “Whenever two batsmen were difficult to shift or something different was wanted someone in the Yorkshire team would say, ‘Put on Maurice to bowl some of those Chinese things.’ ” There is an interesting theory of the origin of the word Chinaman’. Yorkshire captain Cecil Burton observed saying that “It was always thought in Yorkshire that the ball called ‘The Chinaman’ originated from Maurice. A left-arm bowler, he sometimes bowled an enormous off-break from round the wicket which, if not accurately pitched, was easy to see and to get away on the leg-side. In later days, laughing about this, he would say it was a type of ball that might be good enough to get the Chinese out if no one else. Hence this ball became Maurice’s ‘Chinaman’.” Anyway, two years before Walter Robins had got dismissed to Ellis Achong in 1933 and had walked off in a huff, mouthing, “Fancy getting out to a Chinaman”, the papers had already reported about batsmen getting caught off Leyland’s Chinaman. Despite his impressive record with the ball, and the fact that some of his teammates considered him a successor of Rhodes, Leyland perpetually underestimated his own bowling — often claiming “I’d love to bat against myself”. There was probably something in what Leyland said. He had a superb Test record, 2,764 runs at 46.06, of that 1,705 at 56.83 with 7 hundreds in The Ashes, the highest form of the game in those times. However, in all those 41 Tests, he picked up just 6 wickets, at an excruciating high average of 97.50. Denis Compton, perhaps one of the most versatile sportsmen ever, was significantly more successful with his Chinaman bowling in Test cricket. He was of course a peerless batsman, whose very style of willow wizardry brought rays of sunshine into the war-ravaged souls of the post-War Englishmen. 5,807 Test runs at 50.06 and 38,942 in First-Class cricket at 51.85 underline that the shining armour of the splendid knight of English cricket was indeed constructed with its share of steel. Yet, he was a decent left-arm wrist spinner. His 25 Test wickets cost 56.40 apiece, but with some luck he could have won the famous Headingley Test of 1948 through his bowling. For quite a while during that final chase, Don Bradman struggled against his turners and was dropped at slip by Jack Crapp. Arthur Morris was also missed off his bowling during that famed partnership. For all his ability, that amounted to 622 First-Class wickets with three 10-wicket hauls, Compton never considered his bowling more than a parlour trick. Arthur Morris was another batting legend who sometimes turned his arm over to bowl Chinaman. The man considered by many to be the successor of Bradman as the best batsman of Australia at the time of the retirement of the Greatest, Morris was nowhere as regular a bowler as Compton or Leyland. He stuck to scoring runs at the top of the order, remaining one of the best of his era in the late 1940s and then slowly losing his mojo into the next decade. His final figures of 3,533 runs at 46.48 were more than decent, but for someone who averaged 67.77 for 1830 runs from his first 19 Tests, it was a downhill journey. He captured only 12 wickets in First-Class cricket with his Chinaman bowling, and they came at an expensive 49.33 apiece. In Test cricket he bowled in only 6 innings of his 46 Tests. But he did get 2 wickets, finishing with a splendid average of 25. One of them was of his nemesis Alec Bedser, which must have given everyone present at the ground immense pleasure. These three splendid gentlemen, Leyland, Compton and Morris, contributed plenty with the bat, but also kept the flame of left-arm wrist spin burning. They remain in the very select group of men who have bowled in that style in international cricket.

From left: Maurice Leyland, Arthur Morris, Denis Compton © Getty Images[/caption] With the English batsmen proving clueless against the left-arm wrist spin of Kuldeep Yadav, Arunabha Sengupta documents the past and present exponents of the art of the Chinaman (oops, left-arm wrist spin) in international cricket. In this episode he covers some batting greats who experimented with this type of delivery, namely Maurice Leyland, Denis Compton and Arthur Morris. Pitifully, top quality Chinaman bowlers were rare in international cricket. There were Ellis Achong and Chuck Fleetwood-Smith in the 1930s and Lindsay Kline in the late 1950s and early 1960s, along with the wrist-spinning aspect of the genius of Garry Sobers. Apart from that very few Chinaman bowlers plied their trade in the Test world. However, three legendary batsmen did turn their hands to left-arm wrist spin, and all of them did bowl in Test cricket with varying degrees of success. Maurice Leyland, the Yorkshire legend and one of the pillars of the England middle order in the 1930s, was perhaps the most accomplished of the trio as far as Chinaman bowling is concerned. In domestic cricket, he formed a formidable combination for Yorkshire alongside pace bowler Bill Bowes and left-arm spinning maestro Headley Verity. He scored over 33,000 runs in First-Class cricket and captured 466 wickets, and still remains one of the select three men to have scored more than 25,000 runs and captured 400-plus wickets for Yorkshire. The other two are, well, George Hirst and Wilfred Rhodes. Having started his career bowling left-arm orthodox, Leyland decided to change to the style that brought the ball into the right hander. It provided Yorkshire — who boasted names like an elderly Wilfred Rhodes, Roy Kilner, and Hedley Verity amongst them — with something different. He would probably not have got a bowl otherwise. Later Wisden wrote in his obituary: “Whenever two batsmen were difficult to shift or something different was wanted someone in the Yorkshire team would say, ‘Put on Maurice to bowl some of those Chinese things.’ ” There is an interesting theory of the origin of the word Chinaman’. Yorkshire captain Cecil Burton observed saying that “It was always thought in Yorkshire that the ball called ‘The Chinaman’ originated from Maurice. A left-arm bowler, he sometimes bowled an enormous off-break from round the wicket which, if not accurately pitched, was easy to see and to get away on the leg-side. In later days, laughing about this, he would say it was a type of ball that might be good enough to get the Chinese out if no one else. Hence this ball became Maurice’s ‘Chinaman’.” Anyway, two years before Walter Robins had got dismissed to Ellis Achong in 1933 and had walked off in a huff, mouthing, “Fancy getting out to a Chinaman”, the papers had already reported about batsmen getting caught off Leyland’s Chinaman. Despite his impressive record with the ball, and the fact that some of his teammates considered him a successor of Rhodes, Leyland perpetually underestimated his own bowling — often claiming “I’d love to bat against myself”. There was probably something in what Leyland said. He had a superb Test record, 2,764 runs at 46.06, of that 1,705 at 56.83 with 7 hundreds in The Ashes, the highest form of the game in those times. However, in all those 41 Tests, he picked up just 6 wickets, at an excruciating high average of 97.50. Denis Compton, perhaps one of the most versatile sportsmen ever, was significantly more successful with his Chinaman bowling in Test cricket. He was of course a peerless batsman, whose very style of willow wizardry brought rays of sunshine into the war-ravaged souls of the post-War Englishmen. 5,807 Test runs at 50.06 and 38,942 in First-Class cricket at 51.85 underline that the shining armour of the splendid knight of English cricket was indeed constructed with its share of steel. Yet, he was a decent left-arm wrist spinner. His 25 Test wickets cost 56.40 apiece, but with some luck he could have won the famous Headingley Test of 1948 through his bowling. For quite a while during that final chase, Don Bradman struggled against his turners and was dropped at slip by Jack Crapp. Arthur Morris was also missed off his bowling during that famed partnership. For all his ability, that amounted to 622 First-Class wickets with three 10-wicket hauls, Compton never considered his bowling more than a parlour trick. Arthur Morris was another batting legend who sometimes turned his arm over to bowl Chinaman. The man considered by many to be the successor of Bradman as the best batsman of Australia at the time of the retirement of the Greatest, Morris was nowhere as regular a bowler as Compton or Leyland. He stuck to scoring runs at the top of the order, remaining one of the best of his era in the late 1940s and then slowly losing his mojo into the next decade. His final figures of 3,533 runs at 46.48 were more than decent, but for someone who averaged 67.77 for 1830 runs from his first 19 Tests, it was a downhill journey. He captured only 12 wickets in First-Class cricket with his Chinaman bowling, and they came at an expensive 49.33 apiece. In Test cricket he bowled in only 6 innings of his 46 Tests. But he did get 2 wickets, finishing with a splendid average of 25. One of them was of his nemesis Alec Bedser, which must have given everyone present at the ground immense pleasure. These three splendid gentlemen, Leyland, Compton and Morris, contributed plenty with the bat, but also kept the flame of left-arm wrist spin burning. They remain in the very select group of men who have bowled in that style in international cricket.