This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

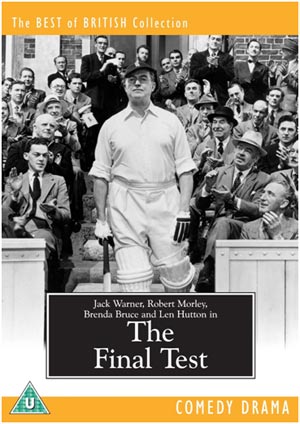

The Final Test — Movie that starred Len Hutton, Denis Compton, Jim Laker, Alec Bedser and Godfrey Evans

‘The Final Test’, released on May 4, 1953, was a movie made with cricket as the central theme.

Written by Arunabha Sengupta

Published: May 12, 2014, 05:35 PM (IST)

Edited: Aug 07, 2014, 04:05 PM (IST)

‘The Final Test’, released on May 4, 1953, was a movie made with cricket as the central theme, in which legends like Len Hutton, Jim Laker, Denis Compton, Godfrey Evans and Alec Bedser appeared as themselves. Arunabha Sengupta looks back at the delightful film which is a must-have in the library of any lover of Test cricket.

The American senator on a goodwill visit to England is shocked to read the doomsday proclamations about the country. It takes him a while to realise that the headlines refer to the on-going Test match against Australia at The Oval.

Thus starts The Final Test, the Anthony Asquith movie released in May, 1953, which combined several glittering stars of the silver screen with some resplendent ones from the cricket field to produce one delightful drama on celluloid. The result is a brilliant tapestry that is moving, funny, even hilarious in parts — poignant enough to touch the soul on occasions.

It is not often that cricket has been used as the theme of a movie with such authenticity and class — before or since. There have been attempts, but there have always been pitfalls. Whenever the on-field action has been reproduced on-screen by actors, the results have remained rather lukewarm. The farcical bowling action of Bodyline’s Bill Voce is just an example. The problems with authenticity have been encountered as often – anachronisms like the six-ball overs, front foot no-ball rule and the six off the last ball in 1893 as depicted in Lagaan, or the slips standing a ridiculous five yards behind the stumps for Larwood in Bodyline.

However, The Final Test does not suffer from any such problem. Much of the cricket on the pitch is played by men like Len Hutton, Cyril Washbrook and Denis Compton — all of whom appear as themselves. The dressing room atmosphere also is hardly contrived, with Jim Laker and Godfrey Evans making the occasional appearances, and Alec Bedser often seen lurking ominously in the background, looking at the action with field glasses.

There was never such a gathering of authentic and legendary sports stars in a fictitious film until Sylvester Stallone assembled Pele, Bobby Moore and the rest of them in Escape to Victory in 1981.

In the other aspects too, the film remains true to the actual world of cricket. John Arlott’s Hampshire drawl is heard over the wireless for much of the 90 minutes. And it is evident that Alf Gover did an excellent job of technical consulting.

The plot revolves around legendary batsman Sam Palmer playing his last Test innings for England. The character is portrayed with admirable poise by the accomplished Jack Warner. To the modern day viewer Warner’s middle-age spread and a face lined with plenty of years may seem rather awkward for a man still playing international cricket. Warner was, after all, 56 at the time of the shooting. However, a glance at some of the cricket photographs from the 1950sis enough to reassure us that the cast and contours are not really too stretched.

[read-also]28206,26823,22901[/read-also]

There is an engaging emotional conflict-essential for any quality drama. Palmer’s teenage son, Reggie, played excellently by Ray Jackson, has set his sights on becoming a poet. He idolises famous playwright Alexander Whitehead, portrayed by the legendary Robert Morley. Reggie tries to fix up a meeting with his hero and unfortunately the appointment coincides with the very day his father wants him to be at The Oval to watch him play his last innings. There are scenes of discord where the son tells his father what he thinks about cricket the game. However, even as the harsh words hurt the father and the cricket loving viewer, the action remains subtle and restrained. And the plot takes a side-splitting turn when Reggie discovers that Whitehead is nuts about cricket and worships his father.

There are plenty of delights in the movie.

The American senator watching the match is stunned by people flocking in for five days, eager to watch a match without a definite result. He is especially confused in finding an unperturbed Brit aghast at the very idea that this test match will generate “excitement”.

There is the moment, both amusing and touching, when Cora the barmaid, played by Brenda Bruce, refuses to serve a client who dares to say Palmer should not be in the team. Sam Palmer’s sister Ethel, superbly portrayed by Adrianne Allen, makes curiously funny attempts to summarise the day’s play while not being aware of the fielding positions.

There is also a not too seriously disguised caricature of Neville Cardus, dictating the events of the day in flamboyant and flourishing prose to his secretary.

The shots of the action on the field, mostly from clippings of old Ashes Tests, are also priceless. The film is actually an extremely good opportunity to watch Compton play the cut and the sweep, while one can enjoy the sight of Hutton pushing one past the covers. There is the nice touch when Compton characteristically runs himself out. Hutton and Compton both look suave and extremely confident while delivering their lines. Ray Lindwall is seen running into bowl quite often. There are plenty of shots of the old stands of The Oval, with double-decker London buses driving past in the background. All through the movie the cricket remains sedate, seldom treated as a tool for heroics such as last ball sixes and cart wheeling stumps.

There is a sub-plot of romance between an aging sportsman and a pretty barmaid and it is handled with care. The script of the great Terence Rattigan remains taut and reaches levels of sublime brilliance in parts. Anthony Asquith’s direction connects and combines several superlative performances into one delectable whole.

The famed Asquith-Rattigan duo, noted for producing serious and sedate dramas such as The Winslow Boy and The Browning Version, supposedly tried their hands at comedy with this movie. One has to say that the final results were splendid.

However, above all else, it is the performance of Morley as the playwright Whitehead that steals the show. From stealthily crawling out of the room with slippers in his mouth, to calling his secretary ‘an expectant vulture’, to asking Palmer to teach him the hook shot, he is a marvel in every frame.

Specifically, two of Morley’s dialogues make the movie a must-watch for all lovers of the traditional game.

[read-also]28577,30053[/read-also]

Driving to The Oval at breakneck speed, he explains to young Reggie Palmer with loads of indignation: “Frightfully dull? Of course cricket’s frightfully dull, that’s the whole point. Any game can be interesting, football, racing, roulette. The measure of the vast superiority of cricket over any other game is that it steadfastly refuses to cater to this boarish craving for excitement. To watch cricket to be thrilled is as stupid as to go to a Chekhov play in search of melodrama.”

And finally, when the two stalwarts, one from the sporting world and one from the literary firmament, meet each other, there is a poignant deadlock. Palmer is overawed by the writing genius and the author is dumbstruck at meeting his sporting hero. It is here that Whitehead launches into the other supreme speech of the movie. He explains why the profession of the cricketer, the non-creative artist, is vastly more rewarding than the trade of the writer: “Is Paganini forgotten? Is Pavlova? Is Nijinsky? … Of course not … the non-creative artist has it over the creative artist all the time because what he has done must get better and better as the years go by until a legend of greatness is built up far beyond the actual proof …Paganini was of course not as great as all that, it’s just that his legend was blown up over the years, just as your legend will grow in another 50 years till you will be enthroned on Olympus between Don Bradman and WG [Grace]. There won’t be a legend about me Mr Palmer, because I have left a record behind for people to read and possibly sneer at.”

An absolutely wonderful summing up of the way legends of cricket grow with the passage of time, wrapped in the gold dust of time — even though the game does leave its own record in scorebooks that the casual fans are more prone to ignore. It is the sumptuous icing on the many delicious layers.

TRENDING NOW

(Arunabha Sengupta is a cricket historian and Chief Cricket Writer at CricketCountry. He writes about the history and the romance of the game, punctuated often by opinions about modern day cricket, while his post-graduate degree in statistics peeps through in occasional analytical pieces. The author of three novels, he can be followed on Twitter at http://twitter.com/senantix)